Relative Requirements

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

Table of Contents

Every developer and designer is different; they have they own skills, interests, and abilities. Similarly, every project is different: where one project might require the utmost focus on performance, the next might have a considerable need for visually striking designs and interactions. While this variety keeps things fresh and exciting, there comes a problem when a developer’s skill-set doesn’t match the requirements of the project, or when teams approach new projects the same way as the last despite the requirements being fundamentally different.

This awkward matrix of skills against requirements can often lead to problems: developers can end up over-engineering simple marketing sites, and designers begin striving for pixel-perfection on quick-and-dirty internal dashboards that just don’t need it. This can lead to internal friction and arguments between team members, but also to excessive cost—spending three days writing the most extensible and elegant code for a campaign site that will be live for a few days is almost impossible to justify.

I tend to, mainly, work with product and app companies; e-commerce, SaaS, etc. These are companies where longevity and performance are usually paramount, and my background in these kinds of environments lends itself very well to helping organisations like these build bigger, faster, and more resilient products.

As well as companies like these, I also work with more traditional client services agencies. These companies still suffer the same problems, but in subtly different ways: they don’t necessarily need the most maintainable or long-lasting code, but they do need to scale and standardise workflows and approaches over various projects at the same time.

Here we have a situation where a developer who’s more inclined to optimise for scale and speed needs to work in an environment where the actual projects themselves might need to focus more on visual treatments and engagement, and much less on architecture and maintainability. This is a prevalent problem across a lot of companies I work with: how do we get the same development team to change their approach when the requirements of the project change, potentially going against their skill-set or even instincts?

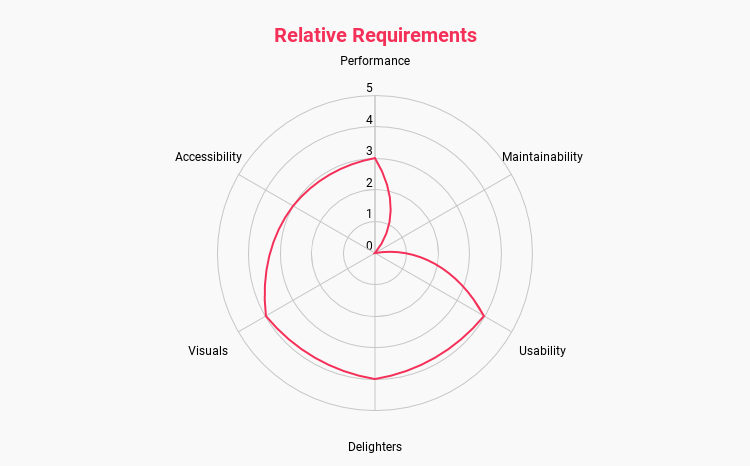

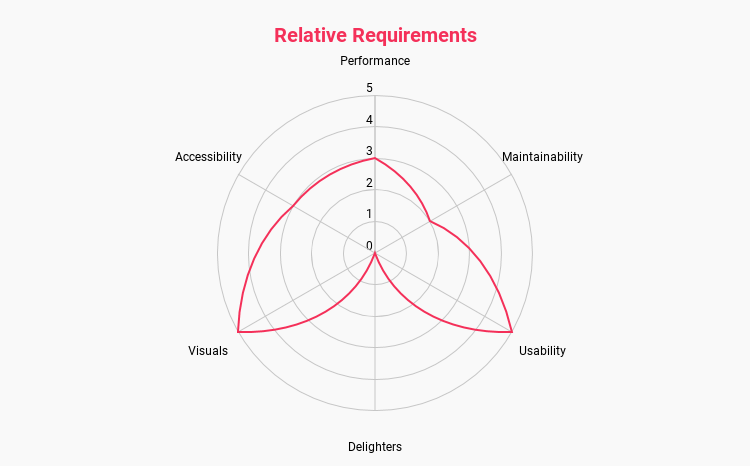

An exercise I came up with a couple of years ago aims to reconcile these issues: Relative Requirements. The aim with Relative Requirements is to take all of the possible traits a project may have (performance, accessibility, visual design, etc.) and give them a relative grading against each other. For example, you may have a project where visual design is paramount, so you assign that four points. Perhaps, on the same project, performance is less important, so we might award that just three points. We might never need to use this project again, so we decide that we should assign zero time and effort to making the code maintainable:

| Trait | Score |

|---|---|

| Performance | 3 |

| Maintainability | 0 |

| Usability | 4 |

| Delighters | 4 |

| Visuals | 4 |

| Accessibility | 3 |

Once we have all of our traits graded against each other, we can plot them on a radar chart which shows us, relatively, which aspects of the build might be more important than the others.

Now, at a glance, anyone can see what the team deem to be the most important traits for this particular project.

Choosing and Grading Your Traits

The traits I outlined above are merely examples: when you draw up your own relative requirements you may end up with a few more of a few less, and that’s fine. The important bit is that the traits are well defined and understood by everybody involved the process. To quickly define the traits I have used:

- Performance: How important is it that this site is fast? For e-commerce sites, it’s probably very important. For marketing or campaign sites, perhaps less so.

- Maintainability: Does this codebase need to last a long time? Do we hope to be adding to it in five years time?

- Usability: Is this the kind of site where we expect continued use? Something like Basecamp or Google Sheets needs to be very usable; a site promoting a new movie maybe needs to consider this a little less.

- Delighters: How important are subtle animations and UI treatments that are absolutely not vital, but do make users smile? These are nice to have, but most products can probably survive without them.

- Visuals: How important is striking visual design? How important is pixel-perfection? For Gov.uk, striking visuals are clearly less important than usability, but if we’re building a site to promote a luxury hotel, we need to be focusing on lavish design.

- Accessibility: Of course, accessibility is always important—we should always be building accessible sites and applications—but accessibility still needs to be subjected to the same grading as everything else.

Feel free to use these traits as-is, or use them as a basis for your own.

N.B. These requirements are relative, which means a score of 2 doesn’t mean something is unimportant, it just means it’s less important than something else. The only way to signify that a trait is truly unimportant is to give it a zero.

Involvement

My advice here is that you should involve as many people as necessary, but as few people as possible. It’s vital that key stakeholders and the designers and developers expected to build the project are present, but inviting too many people brings the risk of prolonged and dragged out discussions.

You could even keep this exercise private to the development team, opting not to involve the client at all. The main idea of Relative Requirements is to get the team to agree on the importance of certain aspects of the build, so it could be kept completely private to them.

Budgeting

One clear problem that we could run into is the urge to just Make everything

a 5!

Of course, this completely undermines the whole exercise, so I advise

setting up a budget that doesn’t allow this to happen. As a general rule, the

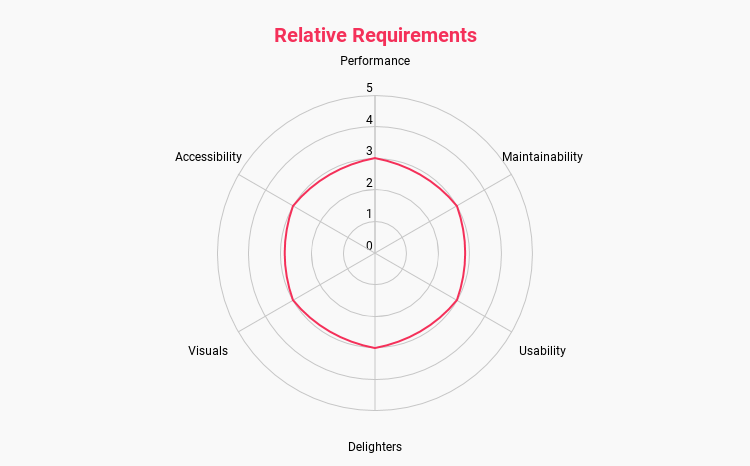

amount of points you can spend is defined by: number of traits × 3.

This means that if we have five traits, we have a total of 15 points to spend.

If we have six traits, our budget is 18 points, and so on.

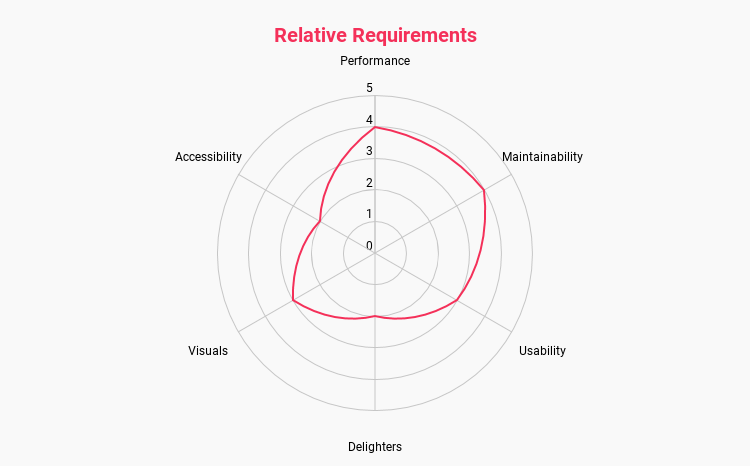

The 3 in this equation is derived from the median score that any trait could have. What this means is that, if we really wanted to, we could award all of our traits a 3 out of 5, allocating all of our budget equally:

Doing this would also undermine the whole process, but starting from here we could begin pulling one trait further out, and decide which traits have to move inward to compensate.

Reading the Chart

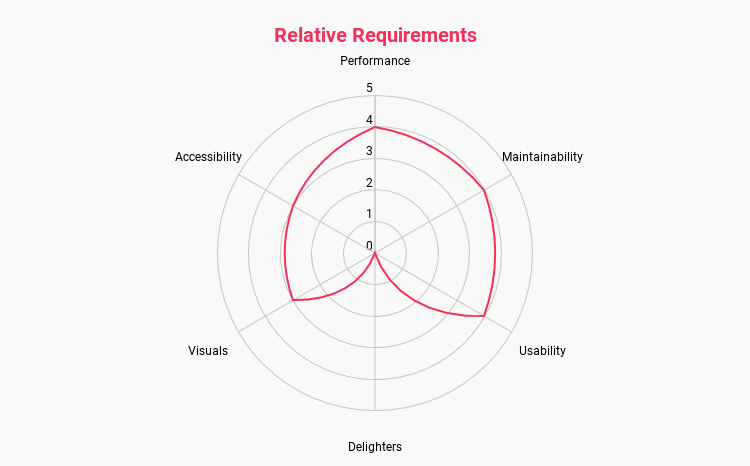

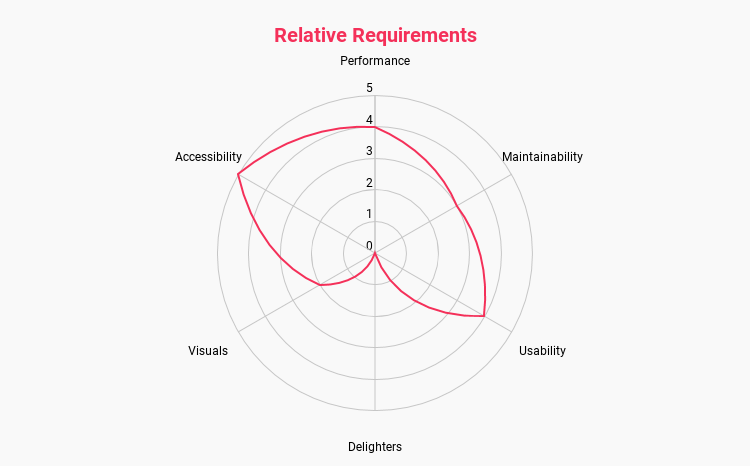

Try to arrange your traits in such a way that the resulting shape of the chart has meaning. You’ll notice that I’ve grouped ‘similar’ traits together, which means a graph that has a heavy weighting to a specific region indicates a general theme: a top- to top-right heavy chart shows we might need our more analytical designers and developers on this project. A bottom- to bottom-left heavy chart shows us that we might need our more creative designers and developers.

Revisiting and Reassessing

It is important that these Relative Requirement charts don’t become a set-it-and-forget-it part of your process: they should be revisited and revised as your project matures.

For example, you might be embarking on an MVP for a potential product: your first chart might put a heavy focus on on usability and visuals, medium on performance, and less so on maintainability (the codebase might get thrown in the bin if the project is not deemed viable) and delighters (they’re not appropriate for an MVP).

If your MVP proves successful, you’re likely to draw up a new strategy for development after this point: you’ll no doubt have a lot of tech debt to clear, and your focus will shift from quick proofs of concept to a more permanent codebase. At this point, you’ll reassess your Relative Requirement and draw up a new chart.

This change signals a shift in priorities, and now might be a good time to set your more creative designers and developers on newer projects, and draft in your more senior or architectural staff to refactor and scale the MVP into a more sustainable project. Again, a key skill here is to be able to quickly read the shapes of your charts in order to, at a glance, ascertain what that general form means.

Outcomes

When implemented effectively, there are a number of advantages and benefits to this model.

The first one is that resource coordinators (project managers, scrum masters, etc.) can quickly see which designers and developers might be best suited to a particular body of work. Don’t assign your senior architects to a highly creative marketing campaign; similarly, don’t put your most creative developer on a long-running SaaS product. You’re unlikely to get the best out of either person, and they’ll likely resent doing the kind of work they’re least suited to.

Another much more useful outcome is conflict resolution. Time and time again I’ve seen design and development teams in arguments because a front-end developer hasn’t implemented animations exactly as intended, or a designer is slowing the process by fighting for pixel-perfection on a project that just doesn’t require it, or a developer is over engineering some JavaScript in pursuit of theoretical purity.

By deciding what we value up-front, we have an agreement that we can look back on in order to help us settle these conflicts and get us back on track again. If we’re working on a short-term marketing campaign, another developer could legitimately call me out if I’ve wasted half a day perfecting the BEM naming used across the project.

Relative Requirements remove the personal aspect of these disagreements and instead focuses on more objective agreements that we made as a team.

Amazing Things Can Happen

I’ll leave you with this:

I ran this exercise with some designers, developers, and members of the business at a large UK fashion retailer (if you live in the UK, you’ve heard of them). My worry was that, as it was a fashion site, we’d be pulling fours and fives on the visual treatments and dropping performance and accessibility to ones or even zeroes. Then something remarkable happened:

Well, our brand is all about providing affordable and non-nonsense clothing to shoppers as quickly and effectively as possible, so if we hit high on performance and usability, we’re perfectly on brand. Let’s prioritise those.

This was a really reassuring moment, and the site continues to be one of the fastest in the e-commerce space.

Try it out1. Let me know how you get on.

-

Here’s a Google Sheets document to make your own. ↩

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

Projects

- ITCSS – coming soon…

Next Appearance

-

Talk & Workshop

WebExpo: Prague (Czech Republic), May 2024

WebExpo: Prague (Czech Republic), May 2024