Base64 Encoding & Performance, Part 1: What’s Up with Base64?

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

Table of Contents

This is the first in a two-part post. Read Part 2.

Prominent performance advice of a few years back simply stated that we should ‘reduce the number of requests we make’. Whilst this is, in general, perfectly sound advice, it’s not without its caveats. We can actually make pages load much more quickly by elegantly spreading our assets over a few more well considered requests, rather than fewer.

One of the touted ‘best practices’ born of this advice was the adoption of Base64 encoding: the act of taking an external asset (e.g. an image) and embedding it directly into the text-resource that would utilise it (e.g. a stylesheet). The upshot of which is that we reduce the number of HTTP requests, and that both assets (e.g. the stylesheet and the image) arrive at the same time. Sounds like a dream, right?

Wrong.

Unfortunately Base64 encoding assets is very much an anti-pattern1. In this article I’m hoping to share some insights as to critical path optimisation, Gzip, and of course, Base64.

Let’s Look at Some Code

The reason I was motivated to write this article is because I’ve just been doing a performance audit for a client, and I came across the very issues I’m about to outline. This is an actual stylesheet from an actual client: things are anonymised, but this is a completely real project.

I ran a quick network profile over the page, and discovered just one stylesheet (which is sorta good in a way because we definitely don’t want to see 12 stylesheet requests), but that stylesheet came in at a whopping 925K after being decompressed and expanded. The actual amount of bytes coming over the wire was substantially less, but still very high at 232K.

As soon as we start seeing stylesheets of that size, we should start panicking. I was relatively certain—without even having to look—that there would be some Base64 in here. That’s not to say that I expected it to be the only factor (plugins, lack of architecture, legacy, etc. are all likely to play a part), but stylesheets that large are usually indicative of Base64. Still:

- Base64 or not, 925K of CSS is terrifying.

- Minifying it only reduces to 759K.

- Gzipping takes us down to a mere 232K. The exact same code compressed down by 693K.

- 232K over the wire is still terrifying.

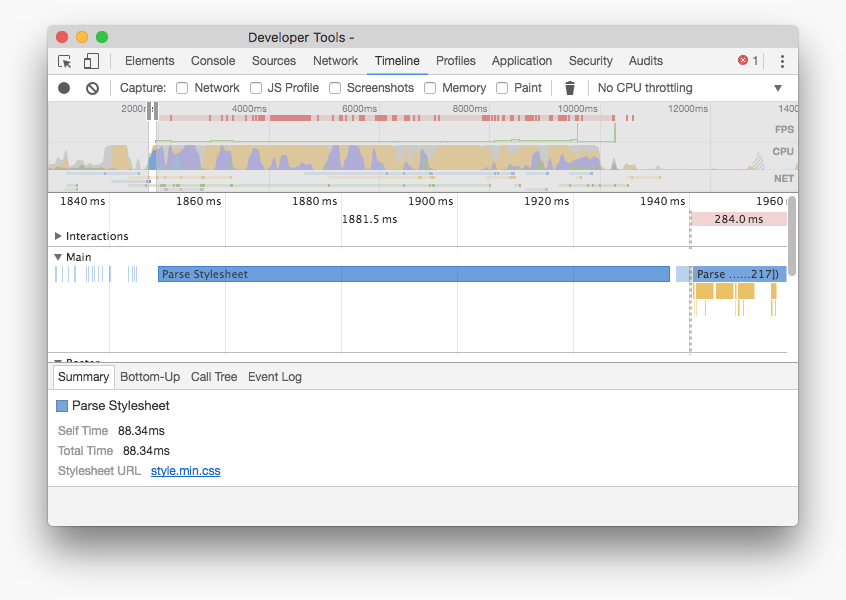

It takes an eye watering 88ms even just to parse a stylesheet of that size. Getting it over the network is just the start of our troubles:

I prettified the file2, saved it to my machine, ran it through CSSO, then ran that minified output through Gzip on its regular setting. This is how I arrived at those numbers, and I was left looking at this:

harryroberts in ~/Sites/<client>/review/code on (master)

» csso base64.css base64.min.css

harryroberts in ~/Sites/<client>/review/code on (master)

» gzip -k base64.min.css

harryroberts in ~/Sites/<client>/review/code on (master)

» ls -lh

total 3840

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 925K 10 Feb 11:23 base64.css

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 759K 10 Feb 11:24 base64.min.css

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 232K 10 Feb 11:24 base64.min.css.gz

The next thing to do was see just how many of these bytes were from Base64

encoded assets. To work this out, I simply (and rather crudely) removed all

lines/declarations that contained data: strings (:g/data:/d3 for the Vim

users reading this). Most of this Base64 encoding was for images/sprites and a

few fonts. I then saved this file as no-base64.css and ran the same

minification and Gzipping over that:

harryroberts in ~/Sites/<client>/review/code on (master)

» ls -lh

total 2648

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 708K 10 Feb 15:54 no-base64.css

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 543K 10 Feb 15:54 no-base64.min.css

-rw-r--r-- 1 harryroberts staff 68K 10 Feb 15:54 no-base64.min.css.gz

In our uncompressed CSS, we’ve managed to lose a whole 217K of Base64. This still leaves us with an alarming amount of CSS (708K is pretty unwieldy), but we’ve managed to get rid of a good 23.45% of our code.

Where things really do get surprising now though is after we’ve Gzipped what’s left. We managed to go from 708K down to just 68K over the wire! That’s a saving of 90.39%. Wow.

Gzip Saves…

Gzip is incredible! It’s probably the single best tool for protecting users from developers. We managed to make a 90% saving over the wire just by compressing our CSS. From 708K down to 68K for free.

…sometimes

However, that’s Gzip working over the non-Base64 encoded version. If we look at the original CSS (the CSS with Base64 encoding), we find that we only made a 74.91% saving.

| Base64? | Gross Size | Compressed Size | Saving |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 925K | 232K | 74.91% |

| No | 708K | 68K | 90.39% |

The difference between the two two options is a staggering 164K (70.68%). We can send 164K less CSS over the wire just by moving those assets out to somewhere more appropriate.

Base64 compresses terribly. Next time somebody tries the ol’ Yeah but

Gzip…

excuse on you, tell them about this (if they’re trying to justify

Base64, that is).

So Why Is Base64 So Bad?

Okay, so we’re pretty clear now that Base64 increases filesize in a manner that Gzip can’t really help us with, but that’s only one small part of the problem. Why are we so scared of this increase in filesize? A single image might weigh well in excess of 232K, so aren’t we better off starting there?

Good question, and I’m glad you mentioned images…

We Need to Talk About Images

In order to understand how bad Base64 is, we first need to understand how good images are. Controversial opinion: images aren’t as bad for performance as you think they are.

Yes, images are a problem. In fact, they’re the number one contributor to page bloat. As of 2 December 2016, images make up around 1623K (or 65.46%) of the average web page. That makes our 232K stylesheet seem like a drop in the ocean by comparison. However, there are fundamental differences between how browsers treat images and stylesheets:

Images do not block rendering; stylesheets do.

A browser will begin to render a page regardless of whether the images have arrived or not. Heck, a browser will render a page even if images never arrive at all! Images are not critical resources, so although they do make up an inordinate amount of bytes over the wire, they are not a bottleneck.

CSS, on the other hand, is a critical resource. Browsers can’t begin rendering a page until they’ve constructed the render tree. Browsers can’t construct the render tree until they’ve constructed the CSSOM. They cannot construct the CSSOM until all stylesheets have arrived, been uncompressed, and parsed. CSS is a bottleneck.

Hopefully now you can see why we’re so scared of CSS bytes: they just serve to delay page rendering, and they leave the user staring at a blank screen. Hopefully, you’ve also realised the painful irony of Base64 encoding images into your CSS files: you just turned hundreds of kilobytes of non-blocking resources into blocking ones in the pursuit of performance. All of those images could have made their way over the network whenever they were ready, but now they’ve been forced to turn up alongside much lighter critical resources. And that doesn’t mean the images arrive sooner; it means the critical CSS arrives later. Could it really get much worse?!

Oh yes, it can.

Browsers are smart. Really smart. They make a lot of performance optimisations for us because—more often than not—they know better. Let’s think about responsive:

.masthead {

background-image: url(masthead-small.jpg);

}

@media screen and (min-width: 45em) {

.masthead {

background-image: url(masthead-medium.jpg);

}

}

@media screen and (min-width: 80em) {

.masthead {

background-image: url(masthead-large.jpg);

}

}

We’ve given the browser three potential images to use here, but it will only download one of them. It works out which one it needs, fetches that one, and leaves the other two untouched.

As soon as we Base64 these images, the bytes for all three get downloaded, effectively tripling (or thereabouts) our overhead. Here’s an actual chunk of CSS from this project (I’ve stripped out the encoded data for obvious reasons, but in full this snippet of code totalled 26K before Gzip; 18K after):

@media only screen and (-moz-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2),

only screen and (-o-min-device-pixel-ratio:2/1),

only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio:2),

only screen and (min-device-pixel-ratio:2),

only screen and (min-resolution:2dppx),

only screen and (min-resolution:192dpi) {

.social-icons {

background-image:url("data:image/png;base64,...");

background-size: 165px 276px;

}

.sprite.weather {

background-image: url("data:image/png;base64,...");

background-size: 260px 28px;

}

.menu-icons {

background-image: url("data:image/png;base64,...");

background-size: 200px 276px;

}

}

All users, whether on retina devices or not (heck, even users with browsers that don’t even support media queries), will be forced to download that extra 18K of CSS before their browser can even begin putting a page together for them.

Base64 encoded assets will always be downloaded, even if they’re never used. That’s wasteful at best, but when you consider that it’s waste that actually blocks rendering, it’s even worse.

And We Need to Talk About Fonts

I’ve only mentioned images so far, but fonts are almost exactly the same except for some nuance around how browsers handle the Flash Of Unstyled/Invisible Text (FOUT or FOIT). Fonts in this project total 166K of uncompressed CSS (124K Gzipped (there’s that awful compression delta again)).

Without derailing the article too much, fonts are also assets that do not naturally live on your critical path, which is great news: your page can render without them. The problem, however, is that browsers handle web fonts differently:

- Chrome and Firefox show no text at all for up to 3 seconds. If the web font arrives within this three seconds the text swaps from invisible to your custom font. If the font still hasn’t arrived after 3 seconds, the text swaps from invisible to whatever fallback(s) you have defined. This is FOIT.

- IE displays the fallback font immediately and then swaps it out for your custom font as soon as it arrives. This is FOUT. This is, in my opinion, the most elegant solution.

- Safari shows invisible text until the font arrives. If the font never arrives, it never shows a fallback. This is FOIT. It’s also an absolute abomination. There’s every chance that your users will never be able to see any text on your page.

In order to get around this, people started Base64 inlining their fonts into their stylesheets: if the CSS and the fonts arrive at the exact same time, then there wouldn’t be a FOIT or a FOUT, because CSSOM construction and font delivery are happening at more or less the same time.

Only, as before, moving your fonts onto the critical path doesn’t speed up their delivery, it just delays your CSS. There are some pretty intelligent font loading solutions out there, but Base64 ain’t one of them.

And We Need to Talk About Caching

Base64 also affects our ability to have more sophisticated caching strategies: by coupling our fonts, images, and styles together, they’re all governed by the same rule. This means that if we change just one hex value in our CSS somewhere—a change that might represent up to six bytes of new data—we have to redownload hundreds of kilobytes of styles, images, and fonts.

In fact, fonts are a really bad offender here: fonts are very, very unlikely to ever change. They’re a very infrequently modified resource. In fact, I just went and checked a long-running project that another client and I are working on: the last change to their CSS was yesterday; the last change to their font files was eight months ago. Imagine forcing a user to redownload those fonts every single time you update anything in your stylesheet.

Base64 encoding means that we can’t cache things independently based on their rate of change, and also means that we have to cache bust unrelated things whenever something else does change. It’s a lose-lose situation.

This is basic separation of concerns: my fonts’ caching should not be dependent on my images’ caching should not be dependent on my styles’ caching.

Okay, so let’s quickly recap:

- Base64 encoding increases filesize in ways that we can’t effectively mitigate (e.g. Gzip). This increase in filesize delays rendering, because it’s happening to a render-blocking resource.

- Base64 encoding also forces non-critical assets onto the critical path. (e.g images, fonts) This means that—in this particular case—instead of needing to download 68K of CSS before we can begin rendering the page, we need to download over 3.4× that amount. We’re just keeping the user waiting for assets that they originally would have never needed to wait for!

- Base64 encoding forces all asset bytes to be downloaded, even if they’ll never be used. This is a waste of resources and, again, it’s happening on our critical path.

- Base64 encoding restricts our ability to cache assets individually; our images and fonts are now bound to the same caching rules as our styles, and vice versa.

All in all, it’s a pretty bleak situation: please avoid Base64.

Data Talks

All of this article was written using things I already know. I didn’t run any tests or have any data: it’s just how browsers work™. However, I decided to go ahead and run some tests to see just what kind of facts and figures we’re looking at. Head over to Part 2 to read more.

-

There are some very exceptional cases in which it may be sensible, but you will be absolutely certain of those cases when they arise. If you’re not absolutely certain, then it probably isn’t one of those cases. Always err on the side of caution and assume that Base64 isn’t the right approach to take. ↩

-

Open the stylesheet in Chrome’s Sources tab, press the

{}icon at the bottom left of the file, done. ↩ -

Run the global command (

:g) across all lines; find lines that containdata:(/data:) and delete them (/d). ↩

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

Projects

- ITCSS – coming soon…

Next Appearance

-

Talk & Workshop

WebExpo: Prague (Czech Republic), May 2024

WebExpo: Prague (Czech Republic), May 2024