By Harry Roberts

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

This article started life as a Twitter thread, but I felt it needed a more permanent spot. You should follow me on Twitter if you don’t already.

I’ve been asked a few times—mostly in workshops—why HTTP/2 (H/2) waterfalls often still look like HTTP/1.x (H/1). Why are things are done in sequence rather than in parallel?

Let’s unpack it!

Fair warning, I am going to oversimplify some terms and concepts. My goal is to illustrate a point rather than explain the protocol in detail.

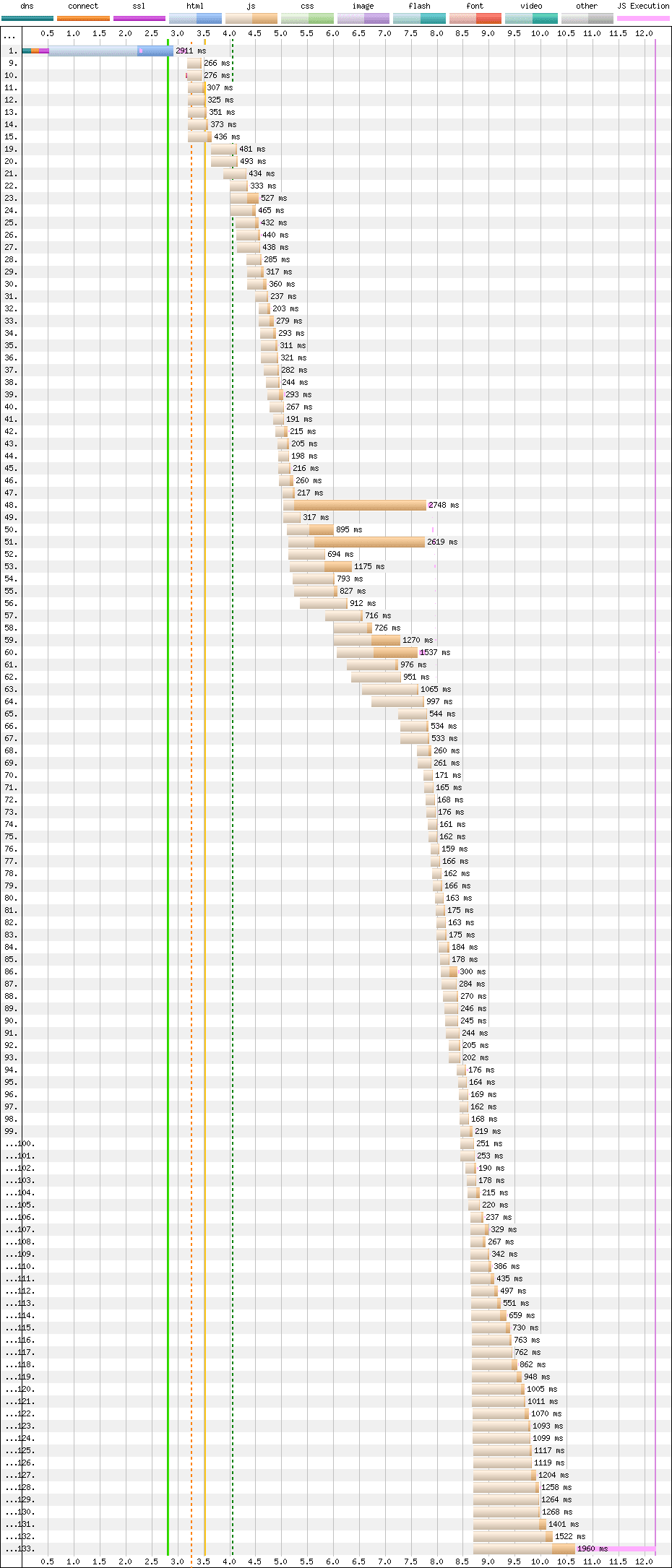

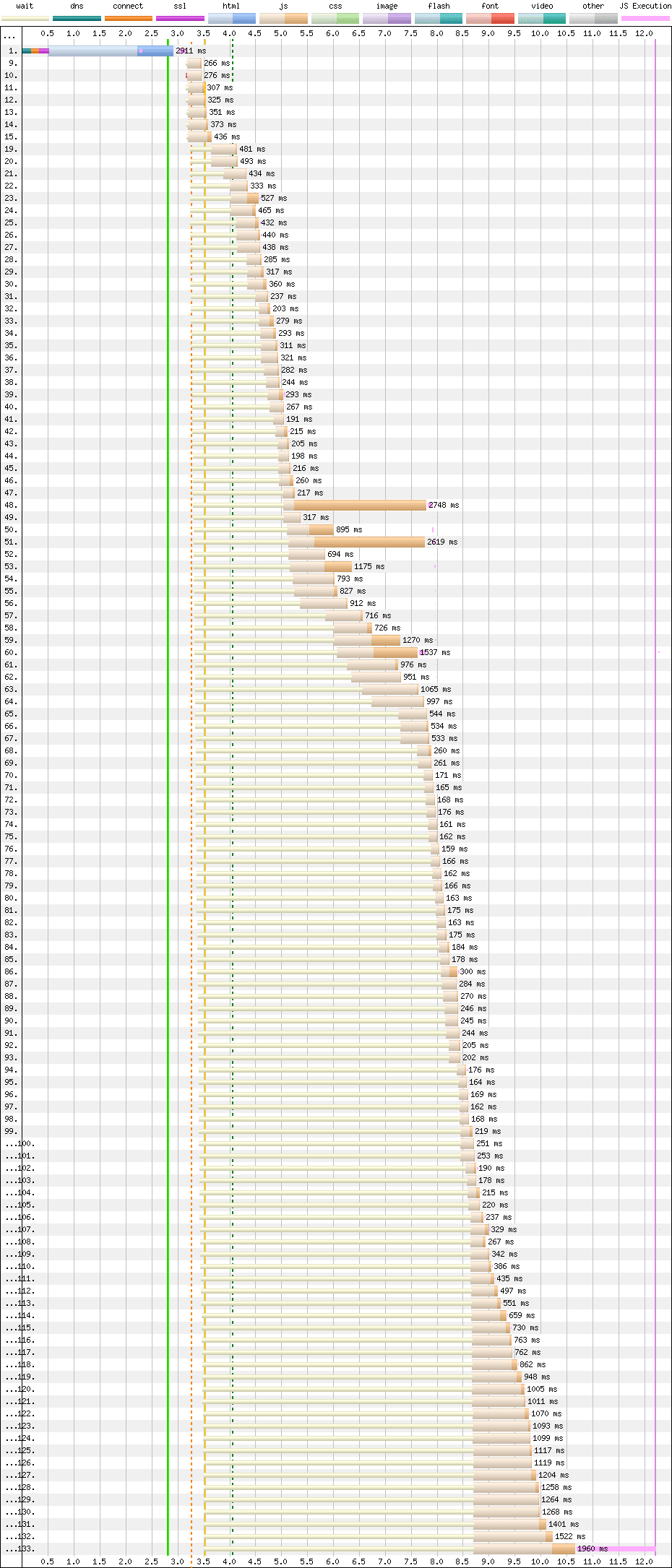

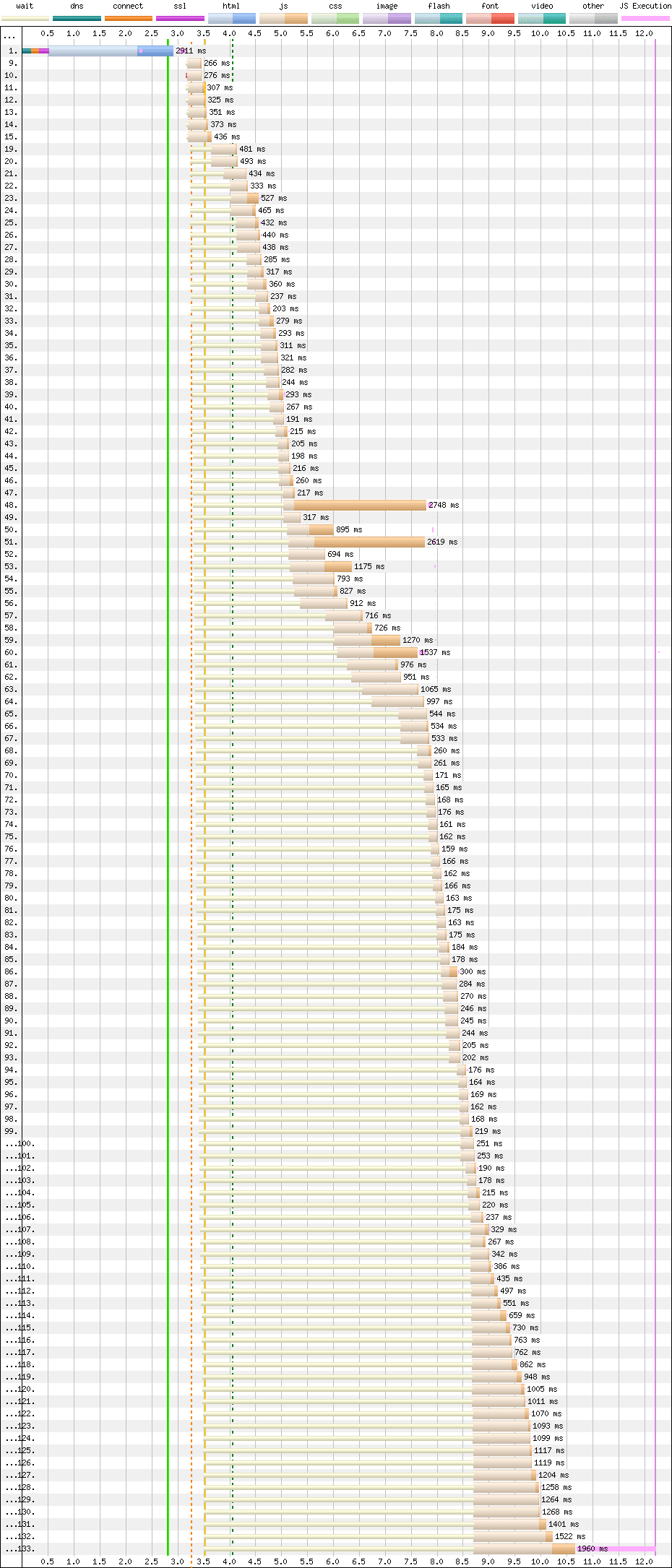

One of the promises of H/2 was infinite parallel requests (up from the historical six concurrent connections in H/1). So why does this H/2-enabled site have such a staggered waterfall? This doesn’t look like H/2 at all!

Things get a little clearer if we add Chrome’s queueing time to the graph. All of these files were discovered at the same time, but their requests were dispatched in sequence.

As a performance engineer, one of the first shifts in thought is that we don’t care only about when resources were discovered or requests were dispatched (the leftmost part of each entry). We also care about when responses are finished (the rightmost part of each entry).

When we stop and think about it, ‘when was a file useful?’ is much more important than ‘when was a file discovered?’. Of course, a late-discovered file will also be late-useful, but really the only thing that matters is usefulness.

With H/2, yes, we can make far more requests at a time, but making more requests doesn’t magically make everything faster. We’re still limited by device and network constraints. We still have finite bandwidth, only now it needs sharing among more files—it just gets diluted.

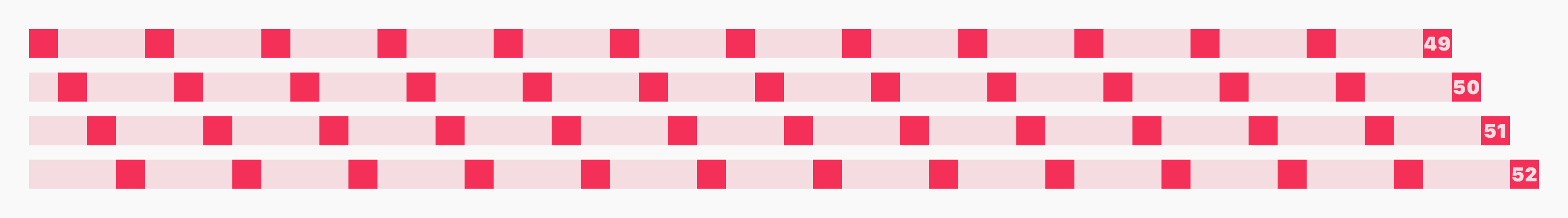

Let’s leave the web and HTTP for a second. Let’s play cards! Taylor, Charlie, Sam, and Alex want to play cards. I am going to deal the cards to the four of them.

These four people and their cards represent downloading four files. Instead of bandwidth, the constant here is that it takes me ONE SECOND to deal one card. No matter how I do it, it will take me 52 seconds to finish the job.

The traditional round-robin approach to dealing cards would be one to Taylor, one to Charlie, one to Sam, one to Alex, and again and again until they’re all dealt. Fifty-two seconds.

This is what that looks like. It took 49 seconds before the first person had all of their cards.

Can you see where this is going?

What if I dealt each person all of their cards at once instead? Even with the same overall 52-second timings, folk have a full hand of cards much sooner.

Thankfully, the (s)lowest common denominator works just fine for a game of cards. You can’t start playing before everyone has all of their cards anyway, so there’s no need to ‘be useful’ much earlier than your friends.

On the web, however, things are different. We don’t want files waiting on the (s)lowest common denominator! We want files to arrive and be useful as soon as possible. We don’t want a file at 49, 50, 51, 52s when we could have 13, 26, 39, 52!

On the web, it turns out that some slightly H/1-like behaviour is still a good idea.

Back to our chart. Each of those files is a deferred JS

bundle, meaning they need to run in

sequence. Because of how everything is scheduled, requested, and prioritised, we

have an elegant pattern whereby files are queued, fetched, and executed in

a near-perfect order!

Queue, fetch, execute, queue, fetch, execute, queue, fetch, execute, queue, fetch, execute, queue, fetch, execute with almost zero dead time. This is the height of elegance, and I love it.

I fondly refer to this whole process as ‘orchestration’ because, truly, this is artful to me. And that’s why your waterfalls look like that.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

I help teams achieve class-leading web performance, providing consultancy, guidance, and hands-on expertise.

I specialise in tackling complex, large-scale projects where speed, scalability, and reliability are critical to success.