I help companies find and fix site-speed issues. Performance audits, training, consultancy, and more.

Core Web Vitals for Search Engine Optimisation: What Do We Need to Know?

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

Table of Contents

- Updates

- Core Web Vitals and SEO

- Site-Speed Is More Than SEO

- Some History

- The Best Content Always Wins

- Core Web Vitals Are Important

- It’s Not Just About Core Web Vitals

- You Don’t Need to Pass FID

- Interaction to Next Paint Doesn’t Matter Yet

- You’re Ranked on Individual URLs

- Search Console Is Gospel

- Ignore Lighthouse and PageSpeed Insights Scores

- Failing Pages Don’t Get Penalised

- Core Web Vitals Are a Tie-Breaker

- There Are No Shades of Good or Failed URLs

- Mobile and Desktop Thresholds Are the Same

- Slow Countries Can Harm Global Rankings

- iOS (and Other) Traffic Doesn’t Count

- Core Web Vitals and Single Page Applications

- We Don’t Know How Much Core Web Vitals Help

- Measuring the Impact of Core Web Vitals on SEO

- So, What Do We Do?!

- Sources

Updates

Stay updated by following this article’s Twitter thread. I will post amendments and updates there.

- 26 July, 2023: iOS (and Other) Traffic Doesn’t Count

Core Web Vitals and SEO

Google’s Core Web Vitals initiative was launched in May of 2020 and, since then, its role in Search has morphed and evolved as roll-outs have been made and feedback has been received.

However, to this day, messaging from Google can seem somewhat unclear and, in places, even contradictory. In this post, I am going to distil everything that you actually need to know using fully referenced and cited Google sources.

Don’t have time to read 5,500+ words? Need to get this message across to your entire company? Hire me to deliver this talk internally.

If you’re happy just to trust me, then this is all you need to know right now:

Google takes URL-level Core Web Vitals data from CrUX into account when deciding where to rank you in a search results page. They do not use Lighthouse or PageSpeed Insights scores. That said, it is just one of many different factors (or signals) they use to determine your placement—the best content still always wins.

To get a ranking boost, you need to pass all relevant Core Web Vitals and everything else in the Page Experience report. Google do strongly encourage you to focus on site speed for better performance in Search, but, if you don’t pass all relevant Core Web Vitals (and the applicable factors from the Page Experience report) they will not push you down the rankings.

All Core Web Vitals data used to rank you is taken from actual Chrome-based traffic to your site. This means your rankings are reliant on your performance in Chrome, even if the majority of your customers are in non-Chrome browsers. However, the search results pages themselves are browser-agnostic: you’ll place the same for a search made in Chrome as you would in Safari as you would in Firefox.

Conversely, search results on desktop and mobile may appear different as desktop searches will use desktop Core Web Vitals data and mobile searches will use mobile data. This means that your placement on each device type is based on your performance on each device type. Interestingly, Google have decided to keep the Core Web Vitals thresholds the same on both device classifications. However, this is the full extent of the segmentation that they make; slow experiences in, say, Australia, will negatively impact search results in, say, the UK.

If you’re a Single-Page Application (SPA), you’re out of luck. While Google have made adjustments to not overly penalise you, your SPA is never really going to make much of a positive impact where Core Web Vitals are concerned. In short, Google will treat a user’s landing page as the source of its data, and any subsequent route change contributes nothing. Therefore, optimise every SPA page for a first-time visit.

The best place to find the data that Google holds on your site is Search Console. While sourced from CrUX, it’s here that is distilled into actionable, Search-facing data.

The true impact of Core Web Vitals on ranking is not fully understood, but investing in faster pages is still a sensible endeavour for almost any reason you care to name.

Now would be a good time to mention: I am an independent web performance consultant—one of the best. I am available to help you find and fix your site-speed issues through performance audits, training and workshops, consultancy, and more. You should get in touch.

For citations, quotes, proof, and evidence, read on…

Site-Speed Is More Than SEO

While this article is an objective look at the role of Core Web Vitals in SEO, I want to take one section to add my own thoughts to the mix. While Core Web Vitals can help with SEO, there’s so much more to site-speed than that.

Yes, SEO helps get people to your site, but their experience while they’re there is a far bigger predictor of whether they are likely to convert or not. Improving Core Web Vitals is likely to improve your rankings, but there are myriad other reasons to focus on site-speed outside of SEO.

I’m happy that Google’s Core Web Vitals initiative has put site-speed on the radar of so many individuals and organisations, but I’m keen to stress that optimising for SEO is only really the start of your web performance journey.

With that said, everything from this point on is talking purely about optimising Core Web Vitals for SEO, and does not take the user experience into account. Ultimately, everything is all, always about the user experience, so improving Core Web Vitals irrespective of SEO efforts should be assumed a good decision.

The Core Web Vitals Metrics

Generally, I approve of the Core Web Vitals metrics themselves (Largest Contentful Paint, First Input Delay, Cumulative Layout Shift, and the nascent Interaction to Next Paint). I think they do a decent job of quantifying the user experience in a broadly applicable manner and I’m happy that the Core Web Vitals team constantly evolve or even replace the metrics in response to changes in the landscape.

I still feel that site owners who are serious about web performance should augment Core Web Vitals with their own custom metrics (e.g. ‘largest content’ is not the same as ‘most important content’), but as off-the-shelf metrics go, Core Web Vitals are the best user-facing metrics since Patrick Meenan’s work on SpeedIndex.

N.B. In March 2024, First Input Delay (FID) will be removed, and Interaction to Next Paint (INP) will take its place. – Advancing Interaction to Next Paint

Some History

Google has actually used Page Speed in rankings in some form or another since as early as 2010:

As part of that effort, today we’re including a new signal in our search ranking algorithms: site speed.

— Using site speed in web search ranking

And in 2018, that was rolled out to mobile:

Although speed has been used in ranking for some time, that signal was focused on desktop searches. Today we’re announcing that starting in July 2018, page speed will be a ranking factor for mobile searches.

— Using page speed in mobile search ranking

The criteria was undefined, and we were offered little more than it applies

the same standard to all pages, regardless of the technology used to build the

page.

Interestingly, even back then, Google made it clear that the best content would always win, and that relevance was still the strongest signal. From 2010:

While site speed is a new signal, it doesn’t carry as much weight as the relevance of a page.

— Using site speed in web search ranking

And again in 2018:

The intent of the search query is still a very strong signal, so a slow page may still rank highly if it has great, relevant content.

— Using page speed in mobile search ranking

In that case, let’s talk about relevance and content…

The Best Content Always Wins

Google’s mission is to surface the best possible response to a user’s query, which means they prioritise relevant content above all else. Even if a site is slow, insecure, and not mobile friendly, it will rank first if it is exactly what a user is looking for.

In the event that there are a number of possible matches, Google will begin to look at other ranking signals to further arrange the hierarchy of results. To this end, Core Web Vitals (and all other ranking signals) should be thought of as tie-breakers:

Google Search always seeks to show the most relevant content, even if the page experience is sub-par. But for many queries, there is lots of helpful content available. Having a great page experience can contribute to success in Search, in such cases.

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

The latter half of that paragraph is of particular interest to us, though: Core Web Vitals do still matter…

Core Web Vitals Are Important

Though it’s true we have to prioritise the best and most relevant content, Google still stresses the importance of site speed if you care about rankings:

We highly recommend site owners achieve good Core Web Vitals for success with Search…

— Understanding Core Web Vitals and Google search results

That in itself is a strong indicator that Google favours faster websites. Furthermore, they add:

Google’s core ranking systems look to reward content that provides a good page experience.

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

Which brings me nicely onto…

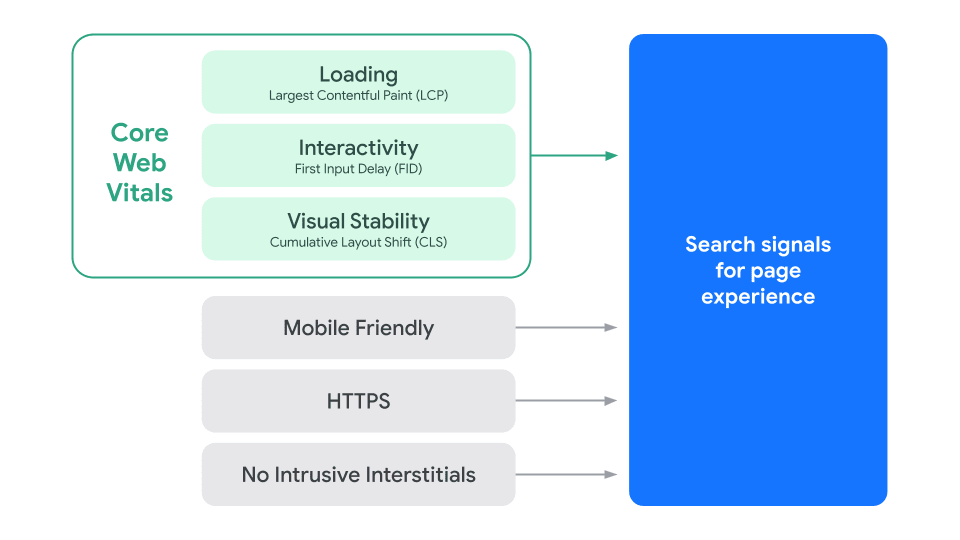

It’s Not Just About Core Web Vitals

What’s this phrase page experience

that we keep hearing about?

It turns out that Core Web Vitals on their own are not enough. Core Web Vitals are a subset of the Page Experience report, and it’s actually this that you need to pass in order to get a boost in rankings.

In May 2020, Google announced the Page Experience report, and, a year later, from June to August 2021, they rolled it out for mobile. Also in August 2021, they removed Safe Browsing and Ad Experience from the report, and in February 2022, they rolled Page Experience out for desktop.

The simplified Page Experience report contains:

- Core Web Vitals

- Largest Contentful Paint

- First Input Delay

- Cumulative Layout Shift

- Mobile Friendly (mobile only, naturally)

- HTTPS

- No Intrusive Interstitials

From Google:

…great page experience involves more than Core Web Vitals. Good stats within the Core Web Vitals report in Search Console or third-party Core Web Vitals reports don’t guarantee good rankings.

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

What this means is we shouldn’t be focusing only on Core Web Vitals, but on the whole suite of Page Experience signals. That said, Core Web Vitals are quite a lot more difficult to achieve than being mobile friendly, which is usually baked in from the beginning of a project.

You Don’t Need to Pass FID

You don’t need to pass First Input Delay. This is because—while all pages will have a Largest Contentful Paint event at some point, and the ideal Cumulative Layout Shift score is none at all—not all pages will incur a user interaction. While rare, it is possible that a URL’s FID data will read Not enough data. To this end, passing Core Web Vitals means Good LCP and CLS, and Good or Not enough data FID.

The URL has Good status in the Core Web Vitals in both CLS and LCP, and Good (or not enough data) in FID

— Page Experience report

Interaction to Next Paint Doesn’t Matter Yet

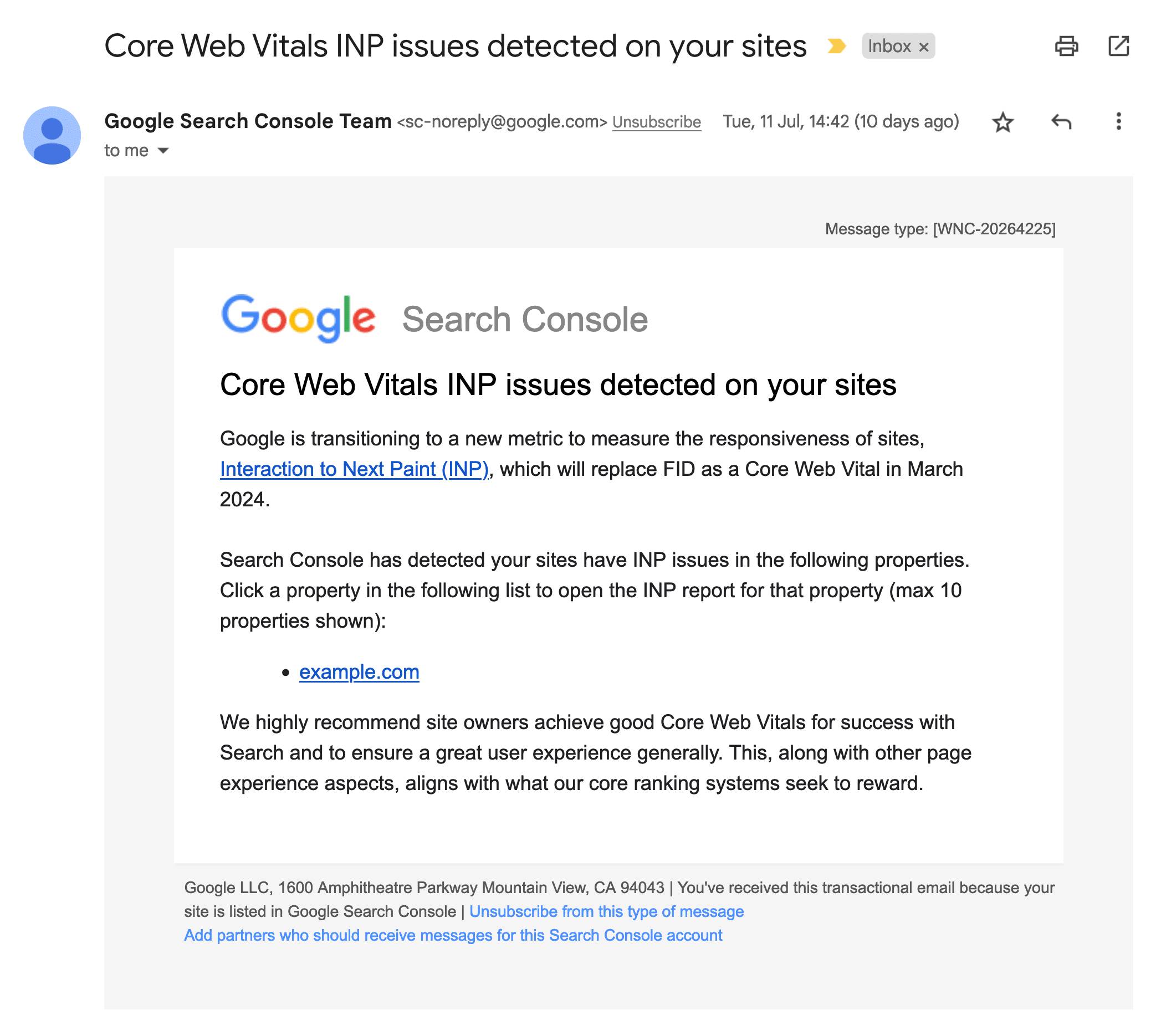

Search Console, and other tools, are surfacing INP already, but it won’t become a Core Web Vital (and therefore part of Page Experience (and therefore part of the ranking signal)) until March 2024:

INP (Interaction to Next Paint) is a new metric that will replace FID (First Input Delay) as a Core Web Vital in March 2024. Until then, INP is not a part of Core Web Vitals. Search Console reports INP data to help you prepare.

— Core Web Vitals report

Incidentally, although INP isn’t yet a Core Web Vital, Search Console has started sending emails warning site owners about INP issues:

You don’t need to worry about it yet, but do make sure it’s on your roadmap.

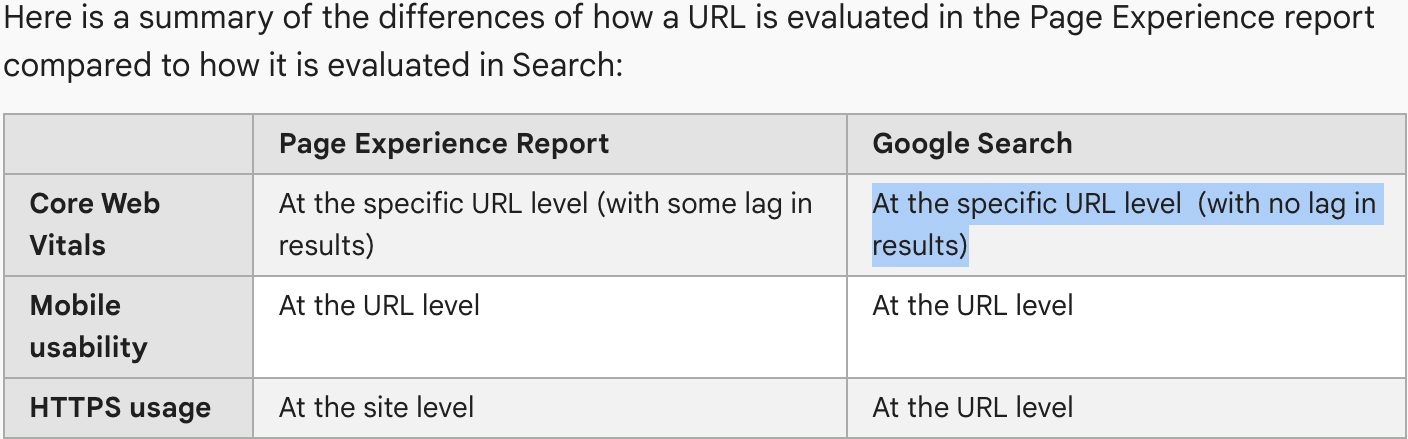

You’re Ranked on Individual URLs

This has been one of the most persistently confusing aspect of Core Web Vitals: are pages ranked on their individual URL status, or the status of the URL Group they live in (or something else entirely)?

It’s done on a per-URL basis:

Google evaluates page experience metrics for individual URLs on your site and will use them as a ranking signal for a URL in Google Search results.

— Page Experience report

There are also URL Groups and larger groupings of URL data:

Our core ranking systems generally evaluate content on a page-specific basis […] However, we do have some site-wide assessments.

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

If there isn’t enough data for a specific URL Group, Google will fall back to an origin-level assessment:

If a URL group doesn’t have enough information to display in the report, Search Console creates a higher-level origin group…

— Core Web Vitals report

This doesn’t tell us why we have URL Groups in the first place. How do they tie into SEO and rankings if we work on a URL- or site-level basis?

My feeling is that it’s less about rankings and more about helping developers troubleshoot issues in bulk:

URLs in the report are grouped [and] it is assumed that these groups have a common framework and the reasons for any poor behavior of the group will likely be caused by the same underlying reasons.

— Core Web Vitals report

URLs are judged on the three Core Web Vitals, which means they could be Good, Needs Improvement, and Poor in each Vital respectively. Unfortunately, URLs are ranked on their lowest common denominator: if a URL is Good, Good, Poor, it’s marked Poor. If it’s Needs Improvement, Good, Needs Improvement, it’s marked Needs Improvement:

The status for a URL group defaults to the slowest status assigned to it for that device type…

— Core Web Vitals report

The URLs that appear in Search Console are non-canonical. This means that

https://shop.com/products/red-bicycle and https://shop.com/bikes/red-bicycle

may both be listed in the report even if their rel=canonical both point to the

same location.

Data is assigned to the actual URL, not the canonical URL, as it is in most other reports.

— Core Web Vitals report

Note that this only discusses the report and not rankings—it is my understanding that this is to help developers find variations of pages that are slower, and not to rank multiple variants of the same URL. The latter would contravene their own rules on canonicalisation:

Google can only index the canonical URL from a set of duplicate pages.

— Canonical

Or, expressed a little more logically, canonical alternative (and noindex)

pages can’t appear in Search in the first place, so there’s little point

worrying about Core Web Vitals for SEO in this case anyway.

I help companies find and fix site-speed issues. Performance audits, training, consultancy, and more.

Interestingly:

Core Web Vitals URLs include URL parameters when distinguishing the page; PageSpeed Insights strips all parameter data from the URL, and then assigns all results to the bare URL.

— Core Web Vitals report

This means that if we were to drop https://shop.com/products?sort=descending

into pagespeed.web.dev, the Core Web Vitals it

presents back would be the data for https://shop.com/products.

Search Console Is Gospel

When looking into Core Web Vitals for SEO purposes, the only real place to consult is Search Console. Core Web Vitals information is surfaced in a number of different Google properties, and is underpinned by data sourced from the Chrome User Experience Report, or CrUX:

CrUX is the official dataset of the Web Vitals program. All user-centric Core Web Vitals metrics will be represented in the dataset.

— About CrUX

And:

The data for the Core Web Vitals report comes from the CrUX report. The CrUX report gathers anonymized metrics about performance times from actual users visiting your URL (called field data). The CrUX database gathers information about URLs whether or not the URL is part of a Search Console property.

— Core Web Vitals report

This is the data that is then used in Search to influence rankings:

The data collected by CrUX is available publicly through a number of tools and is used by Google Search to inform the page experience ranking factor.

— About CrUX

The data is then surfaced to us in Search Console.

Search Console shows how CrUX data influences the page experience ranking factor by URL and URL group.

— CrUX methodology

Basically, the data originates in CrUX, so it’s CrUX all the way down, but it’s in Search Console that Google kindly aggregates, segments, and otherwise visualises and displays the data to make it actionable. Google expects you to look to Search Console to find and fix your Core Web Vitals issues:

Google Search Console provides a dedicated report to help site owners quickly identify opportunities for improvement.

— Evaluating page experience for a better web

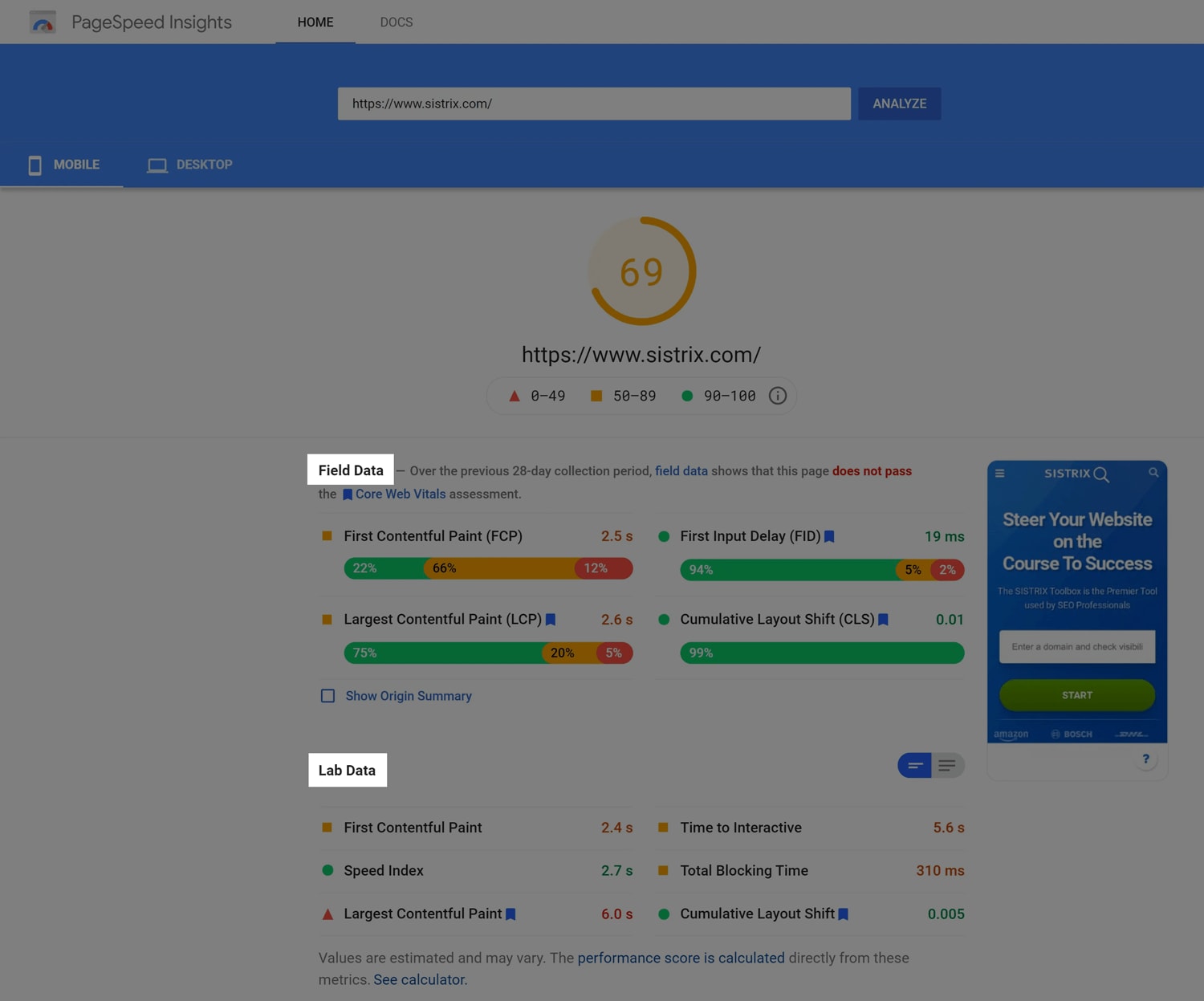

Ignore Lighthouse and PageSpeed Insights Scores

This is one of the most pervasive and definitely the most common misunderstandings I see surrounding site-speed and SEO. Your Lighthouse Performance scores have absolutely no bearing on your rankings. None whatsoever. As before, the data Google use to influence rankings is stored in Search Console, and you won’t find a single Lighthouse score in there.

Frustratingly, there is no black-and-white statement from Google that tells us

we do not use Lighthouse scores in ranking

, but we can prove the

equivalent quite quickly:

The Core Web Vitals report shows how your pages perform, based on real world usage data (sometimes called field data).

– Core Web Vitals report

And:

The data for the Core Web Vitals report comes from the CrUX report. The CrUX report gathers anonymized metrics about performance times from actual users visiting your URL (called field data).

– Core Web Vitals report

That’s two definitive statements saying where the data does come from: the field. So any data that doesn’t come from the field is not counted.

PSI provides both lab and field data about a page. Lab data is useful for debugging issues, as it is collected in a controlled environment. However, it may not capture real-world bottlenecks. Field data is useful for capturing true, real-world user experience – but has a more limited set of metrics.

— About PageSpeed Insights

In the past—and I can’t determine the exact date of the following screenshot—Google used to clearly mark lab and field data in PageSpeed Insights:

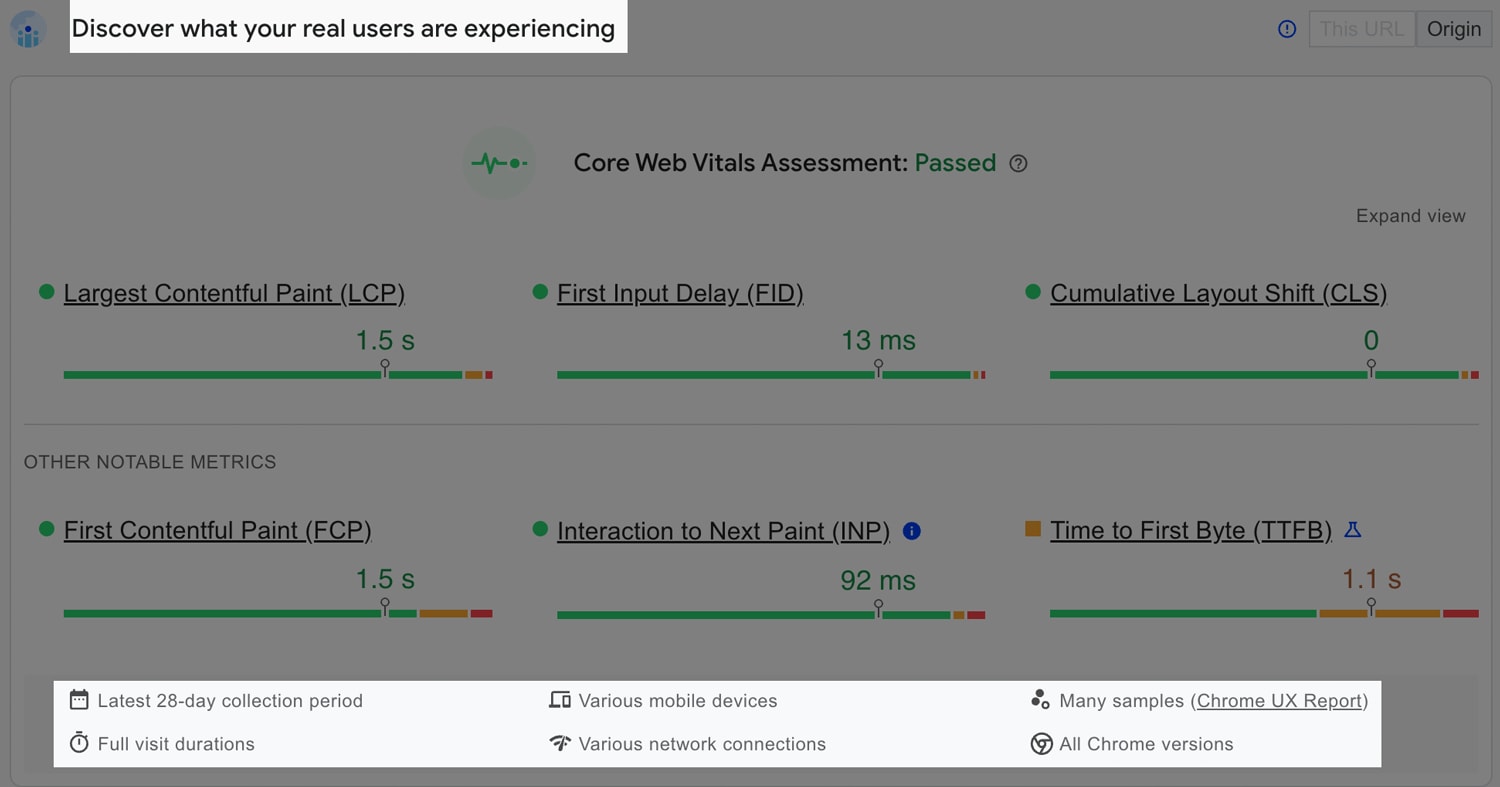

Nowadays, the same data and layout exists, but with much less deliberate wording. Field data is still presented first:

And lab data, from the Lighthouse test we just initiated, beneath that:

So for all there is no definitive warning from Google that we shouldn’t factor Lighthouse Performance scores into SEO, we can quickly piece together the information ourselves. It’s more a case of what they haven’t said, and nowhere have they ever said your Lighthouse/PageSpeed scores impact rankings.

On the subject of things they haven’t said…

Failing Pages Don’t Get Penalised

This is a critical piece of information that is almost impressively-well hidden.

Google tell us that the criteria for a Good page experience are:

- Passes all relevant Core Web Vitals

- No mobile usability issues on mobile

- Served over HTTPS

If a URL achieves Good status, that status will be used as a ranking signal in search results.

Note the absence of similar text under the Failed column. Good URLs’ status will be used as a ranking signal, Failed URLs… nothing.

Good URLs’ status will be used as a ranking signal.

All of Google’s wording around Core Web Vitals is about rewarding Good experiences, and never about suppressing Poor ones:

We highly recommend site owners achieve good Core Web Vitals for success with Search…

— Understanding Core Web Vitals and Google search results

Google’s core ranking systems look to reward content that provides a good page experience.

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

…for many queries, there is lots of helpful content available. Having a great page experience can contribute to success in Search….

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

Note that this is in contrast to their 2018

announcement which stated that The “Speed Update” […] will only affect

pages that deliver the slowest experience to users…

– Speed Update

was a precursor to Core Web Vitals.

This means that failing URLs will not get pushed down the search results page, which is probably a huge and overdue relief for many of you reading this. However…

If one of your competitors puts in a huge effort to improve their Page Experience and begins moving up the search results pages, that will have the net effect of pushing you down.

Put another way, while you won’t be penalised, you might not get to simply stay where you are. Which means…

Core Web Vitals Are a Tie-Breaker

Core Web Vitals really shine in competitive environments, or when users aren’t searching for something that only you could possibly provide. When Google could rank a number of different URLs highly, it defers to other ranking signals to refine its ordering.

…for many queries, there is lots of helpful content available. Having a great page experience can contribute to success in Search, in such cases.

— Understanding page experience in Google Search results

I help companies find and fix site-speed issues. Performance audits, training, consultancy, and more.

There Are No Shades of Good or Failed URLs

Going back to the Good versus Failed columns above, notice that it’s binary—there are no grades of Good or Failed—it’s just one or the other. A URL is considered Failed the moment it doesn’t pass even one of the relevant Core Web Vitals, which means a Largest Contentful Paint of 2.6s is just as bad as a Largest Contentful Paint of 26s.

Put another way, anything other than Good is Failed, so the actual numbers are irrelevant.

Mobile and Desktop Thresholds Are the Same

Interestingly, the thresholds for Good, Needs Improvement, and Poor are the same on both mobile and desktop. Because Google announced Core Web Vitals for mobile first, the same thresholds on desktop should be achieved automatically—it’s very rare that desktop experiences would fare worse than mobile ones. The only exception might be Cumulative Layout Shift in which desktop devices have more screen real estate for things to move around.

For each of the above metrics, to ensure you’re hitting the recommended target for most of your users, a good threshold to measure is the 75th percentile of page loads, segmented across mobile and desktop devices.

— Web Vitals

This does help simplify things a little, with only one set of numbers to remember.

Slow Countries Can Harm Global Rankings

While Google does segment on desktop and mobile—ranking you on each device type proportionate to your performance on each device type—that’s as far at they go. This means that if an experience is Poor on mobile but Good on desktop, any searches for you on desktop will have your fast site taken into consideration.

Unfortunately, that’s as far as their segmentation goes, and even though CrUX does capture country-level data:

…we are expanding the existing CrUX dataset […] to also include a collection of separate country-specific datasets!

— Chrome User Experience Report - New country dimension

…it does not make its way into Search Console or any ranking decision:

Remember that data is combined for all requests from all locations. If you have a substantial amount of traffic from a country with, say, slow internet connections, then your performance in general will go down.

— Core Web Vitals report

Unfortunately, for now at least, this means that if the majority of your paying customers are in a region that enjoys Good experiences, but you have a lot of traffic from regions that suffer Poor experiences, those worse data points may be negatively impacting your success elsewhere.

iOS (and Other) Traffic Doesn’t Count

Core Web Vitals is a Chrome initiative—evidenced by Chrome User Experience Report, among other things. The APIs used to capture the three Core Web Vitals are available in Blink, the browser engine that powers Chromium-based browsers such as Chrome, Edge, and Opera. While the APIs are available to these non-Chrome browsers, only Chrome currently captures data themselves, and populates the Chrome User Experience Report from there. So, Blink-based browsers have the Core Web Vitals APIs, but only Chrome captures data for CrUX.

It should be, hopefully, fairly obvious that non-Chrome browsers such as Firefox or Edge would not contribute data to the Chrome User Experience Report, but what about Chrome on iOS? That is called Chrome, after all?

Unfortunately, while Chrome on iOS is a project owned by the Chromium team, the browser itself does not use Blink—the only engine that can currently capture Core Web Vitals data:

Due to constraints of the iOS platform, all browsers must be built on top of the WebKit rendering engine. For Chromium, this means supporting both WebKit as well as Blink, Chrome’s rendering engine for other platforms.

— Open-sourcing Chrome on iOS!

From Apple themselves:

2.5.6 Apps that browse the web must use the appropriate WebKit framework and WebKit JavaScript.

— App Store Review Guidelines

Any browser on the iOS platform—Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari, you name it—uses WebKit, and the APIs that power Core Web Vitals aren’t currently available there:

From Google themselves:

There are a few notable exceptions that do not provide data to the CrUX dataset […] Chrome on iOS.

— CrUX methodology

The key takeaway here is that Chrome on iOS is actually WebKit under the hood, so capturing Core Web Vitals is not possible at all, for developers or for the Chrome team.

Core Web Vitals and Single Page Applications

If you’re building a Single-Page Application (SPA), you’re going to have to take a different approach. Core Web Vitals was not designed with SPAs in mind, and while Google have made efforts to mitigate undue penalties for SPAs, they don’t currently provide any way for SPAs to shine.

However, properly optimized MPAs do have some advantages in meeting the Core Web Vitals thresholds that SPAs currently do not.

— How SPA architectures affect Core Web Vitals

Core Web Vitals data is captured for every page load, or navigation. Because SPAs don’t have traditional page loads, and instead have route changes, or soft navigations, they don’t emit a standardised way to tell Google that a page has indeed changed. Because of this, Google has no way of capturing reliable Core Web Vitals data for these non-standard soft navigations on which SPAs are built.

The First Page View Is All That Counts

This is critical for optimising SPA Core Web Vitals for SEO purposes. Chrome only captures data from the first page a user actually lands on:

Each of the Core Web Vitals metrics is measured relative to the current, top-level page navigation. If a page dynamically loads new content and updates the URL of the page in the address bar, it will have no effect on how the Core Web Vitals metrics are measured. Metric values are not reset, and the URL associated with each metric measurement is the URL the user navigated to that initiated the page load.

— How SPA architectures affect Core Web Vitals

Subsequent soft navigations are not registered, so you need to optimise every page for a first-time visit.

What is particularly painful here is that SPAs are notoriously bad at first-time visits due to front-loading the entire application. They front-load this application in order to make subsequent page views much faster, which is the one thing Core Web Vitals will not measure. It’s a lose–lose. Sorry.

The (Near) Future Doesn’t Look Bright

Although Google are experimenting with defining soft navigations, any update or change will not be seen in the CrUX dataset anytime soon:

The Chrome User Experience Report (CrUX) will ignore these additional values… — Experimenting with measuring soft navigations

Chrome Have Done Things to Help Mitigate

As soft navigations are not counted, the user’s landing page appears very long lived: as far as Core Web Vitals sees, the user hasn’t ever left the first page they came to. This means Core Web Vitals scores could grow dramatically out of hand, counting n page views against one unfortunate URL. To help mitigate these blind spots inherent in not-using native web platform features, Chrome have done a couple of things to not overly penalise SPAs.

Firstly, Largest Contentful Paint stops being tracked after user interaction:

The browser will stop reporting new entries as soon as the user interacts with the page.

— Largest Contentful Paint (LCP)

This means that the browser won’t keep looking for new LCP candidates as the user traverses soft navigations—it would be very detrimental if a new route loading at 120 seconds fired a new LCP event against the initial URL.

Similarly, Cumulative Layout Shift was modified to be more sympathetic to long-lived pages (e.g. SPAs):

We (the Chrome Speed Metrics Team) recently outlined our initial research into options for making the CLS metric more fair to pages that are open for a long time.

— Evolving the CLS metric

CLS takes the cumulative shifts in the most extreme five-second window, which means that although CLS will constantly update throughout the whole SPA lifecycle, only the worst five-second slice counts against you.

These Mitigations Don’t Help Us Much

No such mitigations have been made with First Input Delay or Interaction to Next Paint, and none of these mitigations change the fact that you are effectively only measured on the first page in a session, or that all subsequent updates to a metric may count against the first URL a visitor encountered.

Solutions are:

- Move to an MPA. It’s probably going to be faster for most use cases anyway.

- Optimise heavily for first visits. This is Core Web Vitals-friendly, but you’ll still only capture one URL’s worth of data per session.

- Cross your fingers and wait. Work on new APIs is promising, and we can only hope that this eventually gets incorporated into CrUX.

We Don’t Know How Much Core Web Vitals Help

Historically, Google have never typically told us what weighting they give to each of their ranking signals. The most insight we got was back in their 2010 announcement:

While site speed is a new signal, it doesn’t carry as much weight as the relevance of a page. Currently, fewer than 1% of search queries are affected by the site speed signal in our implementation and the signal for site speed only applies for visitors searching in English on Google.com at this point. We launched this change a few weeks back after rigorous testing. If you haven’t seen much change to your site rankings, then this site speed change possibly did not impact your site.

— Using site speed in web search ranking

However, this is completely separate to the Core Web Vitals initiative, where we still have zero insight as to how much impact site-speed will have on rankings.

Measuring the Impact of Core Web Vitals on SEO

If Google won’t tell us, can we work it out ourselves?

To the best of my knowledge, no one has done any meaningful study about just how much Good Page Experience might help organic rankings. The only way to really work it out would be take some very solid baseline measurements of a set of failing URLs, move them all into Good, and then measure the uptick in organic traffic to those pages. We’d also need to be very careful not to make any other SEO-facing changes to those URLs for the duration of the experiment.

Anecdotally, I do have one client that sees more than double average click-through rate—and almost the same improvement in average position—for Good Page Experience over the site’s average. For them, the data suggests that Good Page Experience is highly impactful.

So, What Do We Do?!

Search is complicated and, understandably, quite opaque. Core Web Vitals and SEO is, as we’ve seen, very intricate. But, my official advice, at a very high level is:

Keep focusing on producing high-quality, relevant content and work on site-speed because it’s the right thing to do—everything else will follow.

Faster websites benefit everyone: they convert better, they retain better, they’re cheaper to run, they’re better for the environment, and they rank better. There is no reason not to do it.

If you’d like help getting your Core Web Vitals in order, you can hire me.

I help companies find and fix site-speed issues. Performance audits, training, consultancy, and more.

Sources

For this post, I have only taken official Google publications into account. I haven’t included any information from Google employees’ Tweets, personal sites, conference talks, etc. This is because there is no expectation or requirement for non-official sources to edit or update their content as Core Web Vitals information changes.

- Using site speed in web search ranking – Google Search Central Blog – 9 April 2010

- Open-sourcing Chrome on iOS! – Chromium Blog – 31 January, 2017

- Using page speed in mobile search ranking – Google Search Central Blog – 17 January 2018

- Chrome User Experience Report - New country dimension – Chrome Developers – 24 January, 2018

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) – web.dev – 8 August, 2019

- Introducing Web Vitals: essential metrics for a healthy site – Chromium Blog – 5 May, 2020

- Evaluating page experience for a better web – Google Search Central Blog – 28 May, 2020

- Page Experience report – Search Console Help

- Core Web Vitals report – Search Console Help

- Canonical – Search Console Help

- Understanding page experience in Google Search results – Google Search Central

- Understanding Core Web Vitals and Google search results – Google Search Central

- Timing for bringing page experience to Google Search – Google Search Central Blog – 10 November, 2020

- Evolving the CLS metric – web.dev – 7 April, 2021

- More time, tools, and details on the page experience update – Google Search Central Blog – 19 April, 2021

- Simplifying the Page Experience report – Google Search Central Blog – 4 August, 2021

- How SPA architectures affect Core Web Vitals – web.dev – 14 September 2021

- Timeline for bringing page experience ranking to desktop – Google Search Central Blog – 4 November, 2021

- About CrUX – Chrome Developers 23 June, 2022

- CrUX methodology – Chrome Developers – 23 June, 2022

- Experimenting with measuring soft navigations – Chrome Developers – 1 February, 2023

- The role of page experience in creating helpful content – Google Search Central Blog – 19 April, 2023

- Advancing Interaction to Next Paint – web.dev – 10 May, 2023

- About PageSpeed Insights

- App Store Review Guidelines

- LargestContentfulPaint – MDN

- PerformanceEventTiming – MDN

- LayoutShift – MDN

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

By Harry Roberts

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

Projects

- ITCSS – coming soon…

Next Appearance

-

Talk

Devoxx Greece: Athens (Greece), April 2025

Devoxx Greece: Athens (Greece), April 2025