By Harry Roberts

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

A trivial performance optimisation to help speed up third-party or other-origin

requests is to preconnect them: hint that the browser should preemptively open

a full connection (DNS, TCP, TLS) to the origin in question,

for example:

<link rel=preconnect href=https://fonts.googleapis.com>

In the right circumstances, this simple, single line of HTML can make pages hundreds of milliseconds faster! But time and again, I see developers misconfiguring even this most basic of features. Because, as is often the case, there’s much more to this ‘basic feature’ than meets the eye. Let’s dive in…

At the time of writing, the BBC News homepage (in

the UK, at least) has these four preconnects defined early in the <head>:

<link rel=preconnect href=//static.bbc.co.uk crossorigin>

<link rel=preconnect href=//m.files.bbci.co.uk crossorigin>

<link rel=preconnect href=//nav.files.bbci.co.uk crossorigin>

<link rel=preconnect href=//ichef.bbci.co.uk crossorigin>

Readers on narrow screens should know that each of these preconnects

also carries a crossorigin attribute—scroll along to see for yourself!

Note that the BBC use schemeless URLs (i.e. href=//…). I would not

recommend doing this. Always force HTTPS when it’s available.

Having consulted for the BBC a number of times, I know that they make heavy use of internal subdomains to share resources across teams. While this suits developer ergonomics, it’s not great for performance, particularly in cases where the subdomain in question is on the critical path. Warming up connections to important origins is a must for the BBC.

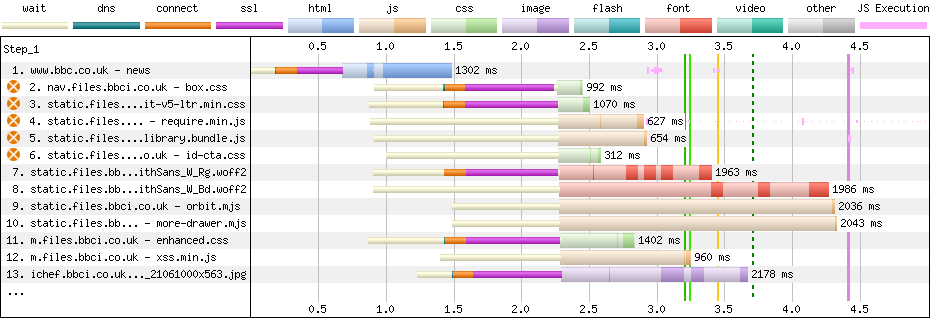

However, a look at a waterfall tells me that none of these preconnects worked!

Above, you can see that the browser discovered references to each of these origins in the first chunk of HTML, before the 1-second mark. This is evidenced by the light white bars that denote ‘waiting’ time—the browser knows it needs the files, but is waiting to dispatch the requests. However, we can also see that the browser didn’t begin network negotiation until closer to the 1.5-second mark, when we begin seeing a tiny slither of green—DNS—followed by the much more costly TCP and TLS. What went wrong?!

preconnectIn the example above, we have five connections to the following four domains (more on that later):

nav.files.bbci.co.uk: On the critical path with render-blocking CSS.static.files.bbci.co.uk: On the critical path with

render-blocking CSS and JS.m.files.bbci.co.uk: On the critical path with render-blocking CSS.

preloaded, which is non-blocking, but it’s then

conditionally applied to the page using document.write() (which is its own

performance faux pas in itself).ichef.bbci.co.uk: Not on the critical path, but does host the

homepage’s LCP element.N.B. For neatness, I am omitting the https:// from

written prose, but it is vital that you include the relevant scheme in your

href attribute. All code examples are complete and correct.

Each of these four origins is vital to the page, so all four would be candidates

for preconnect. However, the BBC aren’t attempting to preconnect

static.files.bbci.co.uk at all; instead, they’re preconnecting

static.bbc.co.uk, which is also used, but isn’t on the critical path. This

feels more like a simple oversight or a typo than anything else.

As a rule, if the origin is important to the page and is used within the first

five seconds of the page-load lifecycle, preconnect it. If the origin is not

important, don’t preconnect it; if it is important but is used more than five

seconds into the page load lifecycle, your priority should be moving it sooner.

Note that important

is very subjective. Your analytics isn’t important;

your chat client isn’t important. Your consent management platform is important;

your image CDN is important.

One easy way to get an overview of early and important origins—and the method I use when advising clients—is to use WebPageTest. Once you’ve run a test, you can head to a Connection View of the waterfall which shows a diagram comprising entries per origin, not per response:

As easy as that—that’s your list of potential origins!

preconnect Too Many Originspreconnect should be used sparingly. Connection overhead isn’t huge, but too

many preconnects that either a) aren’t critical, or b) don’t get used at all,

is definitely wasteful.

Flooding the network with unnecessary preconnects early in the page load

lifecycle can steal valuable bandwidth that could have been given to more

important resources—the overhead of certificates alone can exceed 3KB. Further,

opening and persisting connections has a CPU overhead on both the client and the

server. Lastly, Chrome will close a connection if it isn’t used within the first

10 seconds of being opened, so if you act too soon, you might end up doing it

all over again anyway.

With preconnect, you should strive for as few as possible but as many as

necessary. In fact, I would consider too many preconnects a code smell, and

you probably ought to solve larger issues like self-hosting your static

assets and reducing reliance on third

parties in general.

crossoriginOkay. Now it’s time to learn why the BBC’s preconnects weren’t working!

This is the third time I’ve seen this problem this month (and we’re only nine

days in…). It stems from a misunderstanding around when to use crossorigin.

I get the impression that developers think ‘this request is going to another

origin, so it must need the crossorigin attribute’. But that’s not what the

attribute is for—crossorigin is used to define the CORS policy for the

request. crossorigin=anonymous (or a bare crossorigin attribute) will never

exchange any user credentials (e.g. cookies); crossorigin=use-credentials will

always exchange credentials. Unless you know that you need it, you almost never

need the latter. But when do we use the former?

If the resulting request for a file would be CORS-enabled, you would need

crossorigin on the corresponding preconnect. Unfortunately, CORS isn’t the

most straightforward thing in the world. Fortunately, I have a shortcut…

Firstly, identify a file on the origin that you’re considering preconnecting.

For example, let’s take a look at the BBC’s box.css. In DevTools (or

WebPageTest if you already have one available—you don’t need to run one just for

this task), look at the resource’s request headers:

There it is right there: Sec-Fetch-Mode: no-cors.

The preconnect for nav.files.bbci.co.uk doesn’t currently (I’ll

come back to that shortly) need a crossorigin attribute:

<link rel=preconnect href=https://nav.files.bbci.co.uk>

Let’s look at another request. orbit-v5-ltr.min.css from

static.files.bbci.co.uk also carries a Sec-Fetch-Mode: no-cors request

header, so that won’t need crossorigin either:

<link rel=preconnect href=https://nav.files.bbci.co.uk>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://static.files.bbci.co.uk>

Let’s keep looking.

How about the font BBCReithSans_W_Rg.woff2 also from

static.files.bbci.co.uk?

Hmm. This does need crossorigin as it’s marked Sec-Fetch-Mode: cors. What

do we do here?

Simple!

<link rel=preconnect href=https://nav.files.bbci.co.uk>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://static.files.bbci.co.uk>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://static.files.bbci.co.uk crossorigin>

We just add a second preconnect to open an additional CORS-enabled connection

to static.files.bbci.co.uk. (Remember earlier when the browser had opened five

connections to four origins? One of them was CORS-enabled!)

Let’s keep going and see where we end up…

As it stands, the very specific example of the homepage right now, needs the

following preconnects. Notice that all origins didn’t need crossorigin,

except static.files.bbci.co.uk which needed both:

<link rel=preconnect href=https://nav.files.bbci.co.uk>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://static.files.bbci.co.uk>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://static.files.bbci.co.uk crossorigin>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://m.files.bbci.co.uk>

<link rel=preconnect href=https://ichef.bbci.co.uk>

This feels comfortable! The browser naturally opened five connections, so I’m

happy to see that we’ve also landed on five preconnects; nothing is

unaccounted for.

Sec-* Request HeadersI’d recommend familiarising yourself with the entire suite of Sec-*

headers—they’re incredibly useful debugging tools.

preconnect and DNSBecause DNS is simply IP resolution, it is unaffected by anything CORS-related. This means that:

preconnects to use or omit

crossorigin when you should have actually omitted or used crossorigin,

the DNS step can still be reused—only the

TCP and TLS need

discarding and doing again. That said, DNS is

usually—by far—the fastest part of the process anyway, so speeding it up

while missing out on TCP and

TLS isn’t much of an optimisation to celebrate.preconnect at all, you’ll actually see the browser reusing the

DNS resolution for a subsequent request that

needs a different CORS mode. If you zoom right in on this abridged waterfall,

you’ll see that the second CORS-enabled request to static.files.bbci.co.uk

doesn’t incur any DNS at all:

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

I help teams achieve class-leading web performance, providing consultancy, guidance, and hands-on expertise.

I specialise in tackling complex, large-scale projects where speed, scalability, and reliability are critical to success.