By Harry Roberts

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

One of the more fundamental rules of building fast websites is to optimise your assets, and where text content such as HTML, CSS, and JS are concerned, we’re talking about compression.

The de facto text-compression of the web is Gzip, with around 80% of compressed responses favouring that algorithm, and the remaining 20% use the much newer Brotli.

Of course, this total of 100% only measures compressible responses that actually were compressed—there are still many millions of resources that could or should have been compressed but were not. For a more detailed breakdown of the numbers, see the Compression section of the Web Almanac.

Gzip is tremendously effective. The entire works of Shakespeare weigh in at 5.3MB in plain-text format; after Gzip (compression level 6), that number comes down to 1.9MB. That’s a 2.8× decrease in file-size with zero loss of data. Nice!

Even better for us, Gzip favours repetition—the more repeated strings found in a text file, the more effective Gzip can be. This spells great news for the web, where HTML, CSS, and JS have a very consistent and repetitive syntax.

But, while Gzip is highly effective, it’s old; it was released in 1992 (which certainly helps explain its ubiquity). 21 years later, in 2013, Google launched Brotli, a new algorithm that claims even greater improvement than Gzip! That same 5.2MB Shakespeare compilation comes down to 1.7MB when compressed with Brotli (compression level 6), giving a 3.1× decrease in file-size. Nicer!

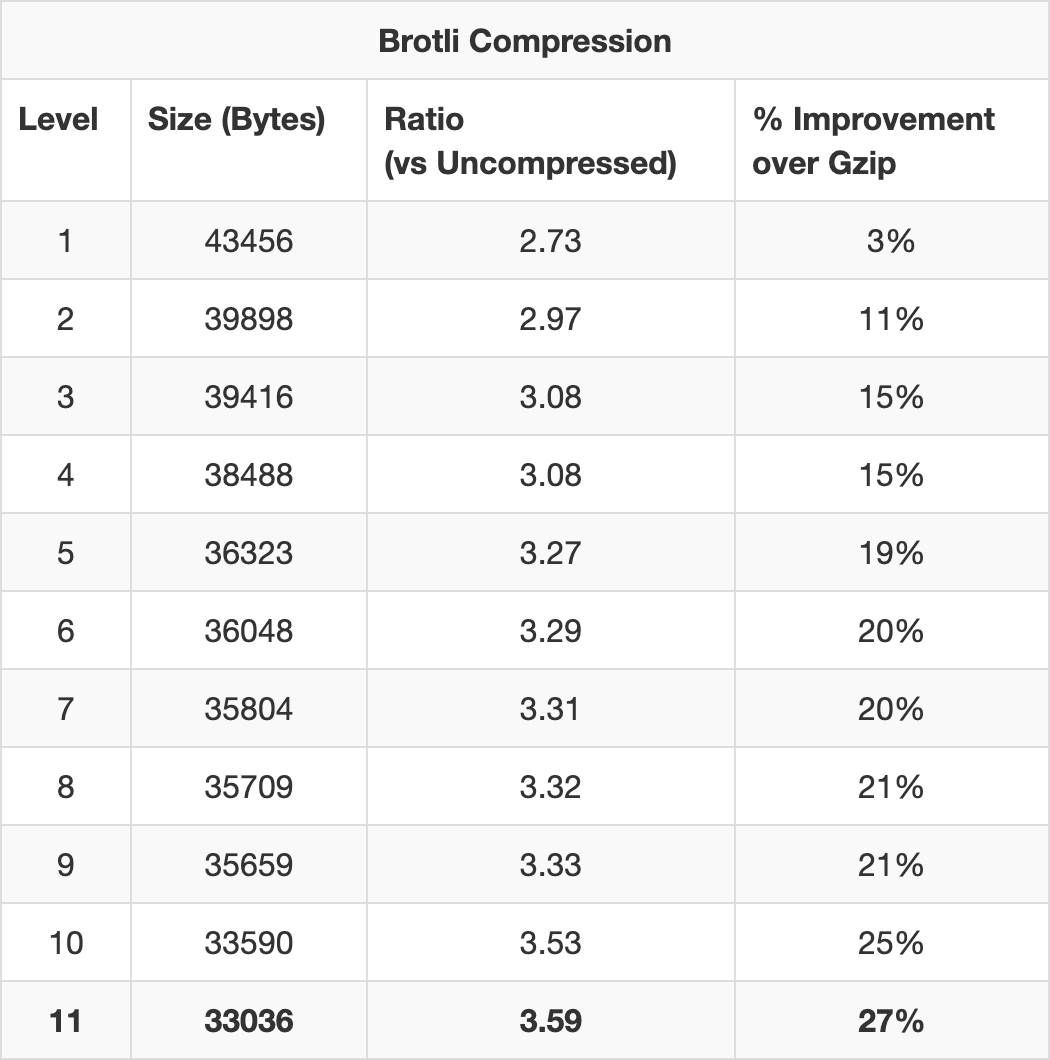

Using Paul Calvano’s Gzip and Brotli Compression Level Estimator!, you’re likely to find that certain files can earn staggering savings by using Brotli over Gzip. ReactDOM, for example, ends up 27% smaller when compressed with maximum-level Brotli compression (11) as opposed to with maximum-level Gzip (9).

And speaking purely anecdotally, moving a client of mine from Gzip to Brotli led to a median file-size saving of 31%.

So, for the last several years, I, along with other performance engineers like me, have been recommending that our clients move over from Gzip and to Brotli instead.

Browser Support: A brief interlude. While Gzip is so widely

supported that Can I Use doesn’t even list tables for it (This HTTP header is

supported in effectively all browsers (since IE6+, Firefox 2+, Chrome 1+

etc)

), Brotli currently enjoys 93.17% worldwide

support at the time of writing, which is

huge! That said, if you’re a site of any reasonable size, serving uncompressed

resources to over 6% of your customers might not sit too well with you. Well,

you’re in luck. The way clients advertise their support for a particular

algorithm works in a completely progressive manner, so users who can’t accept

Brotli will simply fall back to Gzip. More on this later.

For the most part, particularly if you’re using a CDN, enabling Brotli should just be the flick of a switch. It’s certainly that simple in Cloudflare, who I run CSS Wizardry through. However, a number of clients of mine in the past couple of years haven’t been quite so lucky. They were either running their own infrastructure and installing and deploying Brotli everywhere proved non-trivial, or they were using a CDN who didn’t have readily available support for the new algorithm.

In instances where we were unable to enable Brotli, we were always left

wondering What if…

So, finally, I’ve decided to attempt to quantify the

question: how important is it that we move over to Brotli?

Usually, sure! Making a file smaller will make it arrive sooner, generally speaking. But making a file, say, 20% smaller will not make it arrive 20% earlier. This is because file-size is only one aspect of web performance, and whatever the file-size is, the resource is still sat on top of a lot of other factors and constants—latency, packet loss, etc. Put another way, file-size savings help you to cram data into lower bandwidth, but if you’re latency-bound, the speed at which those admittedly fewer chunks of data arrive will not change.

Taking a very reductive and simplistic view of how files are transmitted from server to client, we need to look at TCP. When we receive a file from a sever, we don’t get the whole file in one go. TCP, upon which HTTP sits, breaks the file up into segments, or packets. Those packets are sent, in batches, in order, to the client. They are each acknowledged before the next series of packets is transferred until the client has all of them, none are left on the server, and the client can reassemble them into what we might recognise as a file. Each batch of packets gets sent in a round trip.

Each new TCP connection has no way of knowing what bandwidth it currently has available to it, nor how reliable the connection is (i.e. packet loss). If the server tried to send a megabyte’s worth of packets over a connection that only has capacity for one megabit, it’s going to flood that connection and cause congestion. Conversely, if it was to try and send one megabit of data over a connection that had one megabyte available to it, it’s not gaining full utilisation and lots of capacity is going to waste.

To tackle this little conundrum, TCP utilises a mechanism known as slow start. Each new TCP connection limits itself to sending just 10 packets of data in its first round trip. Ten TCP segments equates to roughly 14KB of data. If those ten segments arrive successfully, the next round trip will carry 20 packets, then 40, 80, 160, and so on. This exponential growth continues until one of two things happens:

This simple, elegant strategy manages to balance caution with optimism, and applies to every new TCP connection that your web application makes.

Put simply: your initial bandwidth capacity on a new TCP connection is only about 14KB. Or roughly 11.8% of uncompressed ReactDom; 36.94% of Gzipped ReactDom; or 42.38% of Brotlied ReactDom (both set to maximum compression).

Wait. The leap from 11.8% to 36.94% is pretty notable! But the change from 36.94% to 42.38% is much less impressive. What’s going on?

| Round Trips | TCP Capacity (KB) | Cumulative Transfer (KB) | ReactDom Transferred By… |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 14 | |

| 2 | 28 | 42 | Gzip (37.904KB), Brotli (33.036KB) |

| 3 | 56 | 98 | |

| 4 | 112 | 210 | Uncompressed (118.656KB) |

| 5 | 224 | 434 |

Both the Gzipped and Brotlied versions of ReactDom fit into the same round-trip bucket: just two round trips to get the full file transferred. If all round trip times (RTT) are fairly uniform, this means there’s no difference in transfer time between Gzip and Brotli here.

The uncompressed version, on the other hand, takes a full two round trips more to be fully transferred, which—particularly on a high latency connection—could be quite noticeable.

The point I’m driving at here is that it’s not just about file-size, it’s about TCP, packets, and round trips. We don’t just want to make files smaller, we want to make them meaningfully smaller, nudging them into lower round trip buckets.

This means that, in theory, for Brotli to be notably more effective than Gzip, it will need to be able to compress files quite a lot more aggressively so as to move it beneath round trip thresholds. I’m not sure how well it’s going to stack up…

It’s worth noting that this model is quite aggressively simplified, and there are myriad more factors to take into account: is the TCP connection new or not, is it being used for anything else, is server-side prioritisation stop-starting transfer, do H/2 streams have exclusive access to bandwidth? This section is a more academic assessment and should be seen as a good jump-off point, but consider analysing the data properly in something like Wireshark, and also read Barry Pollard’s far more forensic analysis of the magic 14KB in his Critical Resources and the First 14 KB – A Review.

This rule also only applies to brand new TCP connections, and any files fetched over primed TCP connections will not be subject to slow start. This brings forth two important points:

| Round Trips | TCP Capacity (KB) | Cumulative Transfer (KB) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 14 |

| 2 | 28 | 42 |

| 3 | 56 | 98 |

| 4 | 112 | 210 |

| 5 | 224 | 434 |

| 6 | 448 | 882 |

| 7 | 896 | 1,778 |

| 8 | 1,792 | 3,570 |

| 9 | 3,584 | 7,154 |

| 10 | 7,168 | 14,322 |

| … | … | … |

| 20 | 7,340,032 | 14,680,050 |

By the end of 10 round trips, we have a TCP capacity of 7,168KB and have already

transferred a cumulative 14,322KB. This is more than adequate for casual web

browsing (i.e. not torrenting streaming Game of Thrones). In actual fact,

what usually happens here is that we end up loading the entire web page and all

of its subresources before we even reach the limit of our bandwidth. Put another

way, your 1Gbps1 fibre line won’t make your day-to-day browsing feel much

faster because most of it isn’t even getting used.

By 20 round trips, we’re theoretically hitting a capacity of 7.34GB.

Okay, yeah. That all got a little theoretical and academic. I started off this whole train of thought because I wanted to see, realistically, what impact Brotli might have for real websites.

The numbers so far show that the difference between no compression and Gzip are vast, whereas the difference between Gzip and Brotli are far more modest. This suggests that while the nothing to Gzip gains will be noticeable, the upgrade from Gzip to Brotli might perhaps be less impressive.

I took a handful of example sites in which I tried to cover sites that were a good cross section of:

With those requirements in place, I grabbed a selection of origins and began testing:

I wanted to keep the test simple, so I grabbed only:

FCP feels like a real-world and universal enough metric to apply to any site,

because that’s what people are there for—content. Also because Paul

Calvano said so, and he’s smart: Brotli

tends to make FCP faster in my experience, especially when the critical CSS/JS

is large.

Here’s a bit of a dirty secret. A lot of web performance case studies—not all,

but a lot—aren’t based on improvements, but are often extrapolated and inferred

from the opposite: slowdowns. For example, it’s much simpler for the BBC to say

that they lose an additional 10% of

users for every

additional second it takes for their site to load

than it is to work out

what happens for a 1s speed-up. It’s much easier to make a site slower, which is

why so many people seem to be so good at it.

With that in mind, I didn’t want to find Gzipped sites and then try and somehow Brotli them offline. Instead, I took Brotlied websites and turned off Brotli. I worked back from Brotli to Gzip, then Gzip to to nothing, and measured the impact that each option had.

Although I can’t exactly hop onto LinkedIn’s servers and disable Brotli, I can

instead choose to request the site from a browser that doesn’t support Brotli.

And although I can’t exactly disable Brotli in Chrome, I can hide from the

server the fact that Brotli is supported. The way a browser advertises its

accepted compression algorithm(s) is via the content-encoding request header,

and using WebPageTest, I can define my own. Easy!

accept-encoding: randomstring.accept-encoding: gzip.I can then verify that things worked as planned by checking for the

corresponding (or lack of) content-encoding header in the response.

As expected, going from nothing to Gzip has massive reward, but going from Gzip to Brotli was far less impressive. The raw data is available in this Google Sheet, but the things we mainly care about are:

All values are median; ‘Size’ refers to HTML, CSS, and JS only.

Gzip made files 72% smaller than not compressing them at all, but Brotli only saved us an additional 5.7% over that. In terms of FCP, Gzip gave us a 23% improvement when compared to using nothing at all, but Brotli only gained us an extra 3.5% on top of that.

While the results to seem to back up the theory, there are a few ways in which I could have improved the tests. The first would be to use a much larger sample size, and the other two I shall outline more fully below.

In my tests, I disabled Brotli across the board and not just for the first party origin. This means that I wasn’t measuring solely the target’s benefits of using Brotli, but potentially all of their third parties as well. This only really becomes of interest to us if a target site has a third party on their critical path, but it is worth bearing in mind.

When we talk about compression, we often discuss it in terms of best-case scenarios: level-9 Gzip and level-11 Brotli. However, it’s unlikely that your web server is configured in the most optimal way. Apache’s default Gzip compression level is 6, but Nginx is set to just 1.

Disabling Brotli means we fall back to Gzip, and given how I am testing the sites, I can’t alter or influence any configurations or fallbacks’ configurations. I mention this because two sites in the test actually got larger when we enabled Brotli. To me this suggests that their Gzip compression level was set to a higher value than their Brotli level, making Gzip more effective.

Compression levels are a trade-off. Ideally you’d like to set everything to the highest setting and be done, but that’s not really practical—the time taken on the server to do that dynamically would likely nullify the benefits of compression in the first place. To combat this, we have two options:

It would seem that, realistically, the benefits of Brotli over Gzip are slight.

If enabling Brotli is as simple as flicking a checkbox in the admin panel of your CDN, please go ahead and do it right now: support is wide enough, fallbacks are simple, and even minimal improvements are better than none at all.

Where possible, upload precompressed static assets to your web server with the highest possible compression setting, and use something more middle-ground for anything dynamic. If you’re running on Nginx, please ensure you aren’t still on their pitiful default compression level of 1.

However, if you’re faced with the prospect of weeks of engineering, test, and

deployment efforts to get Brotli live, don’t panic too much—just make sure you

have Gzip on everything that you can compress (that includes your .ico and

.ttf files, if you have any).

I guess the short version of the story is that if you haven’t or can’t enable Brotli, you’re not missing out on much.

That 1Gbps you’re getting sold actually equates to 0.125GBps. ISPs hide their false advertising in plain sight. ↩

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

I help teams achieve class-leading web performance, providing consultancy, guidance, and hands-on expertise.

I specialise in tackling complex, large-scale projects where speed, scalability, and reliability are critical to success.