My Trello workflow

Written by Harry Roberts on CSS Wizardry.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

Table of Contents

I’m a huge fan and proponent of working agile and the various schools of thought around it: scrum; Kanban; MVP; product-led, iterative development; releasing little, early, and often; you name it.

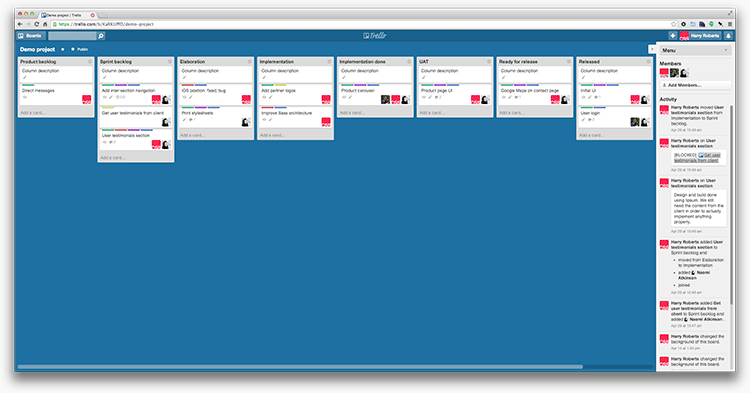

I recently shared a public demo of the Trello board that I use for development work—just one small aspect of running an agile project. This post won’t teach you anything about running an agile project or team—you can hire me for that—but it might help you set up a decent Kanban board if you already know how to work agile.

You will probably want to have this Trello board open as you read this article, because things will make a lot more sense if you can have a look around for yourselves: trello.com/b/demo-project

Trello

Personally, I really like a physical Kanban board—using magnets and different coloured index cards—but given that I work with distributed teams, and I work from various locations, a physical board just doesn’t work. We had physical boards at Sky, and they were great—10′ long, and perfect for standing around and discussing during stand-ups.

Because I can’t have a physical board, I use Trello, which is an amazing, free, online Kanban board produced by Fog Creek. If you don’t already have a Trello account, you should definitely get one.

The Columns

The most fundamental part of any Trello board is its columns. At Sky, we had around 18 (yes, one-eight) columns on our board, but they worked—they all had a place and a purpose. Sky’s board covered everything from design to DevOps, engineering to acceptance testing, and everything in between.

My boards are typically a lot less extensive, with eight columns, but—as is the agile way—I can scale them up or down depending on what comes my way. Whichever way you look at it, it’s fairly safe to say that the standard To Do, Doing, and Done columns aren’t up to the job.

To Do, Doing, Done

The traditional—and Trello’s default—column structure is a simple To Do, Doing, and Done. This sums up the general sentiment of a development project, but it’s a vast oversimplification of the process. There are different definitions and states of done, for a start, and various people have different jobs to do at different stages of a sprint. My current setup has the following columns, which I will explain in more detail:

- Product backlog

- Sprint backlog

- Elaboration

- Implementation

- Implementation done

- (User) acceptance testing

- Ready for release

- Released

Product Backlog

The Product backlog is the product’s wishlist: This is the stuff that we might want to build at some point. This can be seen as a dumping ground of ideas and nice-to-haves, and the client is usually allowed to add and expand on things in this column. It has nothing to do with the current sprint, but will be the source of tasks for all future sprints.

Sufficiently mature products/projects might have their own Roadmap Trello board elsewhere.

Sprint Backlog

The Sprint backlog is the stuff that the team has committed to building in this current sprint. It is sourced from the cards in the Product backlog and should amount to one sprint’s worth of one scrum’s work. The cards in this column should be decided on and prioritised by the entire scrum: clients/Product Owners should steer product and feature decisions, and the development team would decide on a suitable workload. Priority would usually be proposed by the Product Owner, but ultimately decided by the whole scrum.

Elaboration

A lot of the time, tasks might need investigating or discussing before you can start working on them properly. For example, you might need to read up on various different APIs before deciding which—if any—you might use for development.

A good real life example would be the card I dealt with just today. We’re working on a very rapidly-developed project for the NHS, and phase one came together very quickly. I created a card called Performance improvements in which I wanted to introduce ImageOptim-CLI and CSSO to our automated build process (given the time-constraints of P1, we ran ImageOptim-CLI manually, and given that the CSS only weighed 7.5KB when minified regularly, CSSO was of little use to us anyway), but it was a task that had to be discussed: Was the time-cost of integrating CSSO going to save us a substantial enough amount of bytes over the wire? Could we run ImageOptim-CLI as a Git-hook? This was the elaboration phase that this card went through before we decided to implement any work, if at all.

Anything in the elaboration column is typically an investigative or discussion piece, and a lot of—if not most—cards will never need to pass through this column.

Implementation

Implementation is just another word for Doing: we’re basically just implementing any work we’ve decided to do. This could be getting content from a client, designing a user-profile page, building out our architecture, setting up live environments, anything.

Implementation should cover the bare minimum to get that task considered complete: testing and approval are separate tasks to actually implementing the feature.

Implementation Done

This is probably the one column that everyone’s board could use right away. No matter what process you have already, this column is so useful. Implementation done is basically a column for work that has been completed by a designer or developer, but isn’t yet being reviewed, tested, or put live. The work is done, but the whole task isn’t. This column serves a few purposes.

Firstly, it allows a developer to do their immediate tasks and then move on to the next thing without having to worry about getting a Product Owner’s nod of approval, or a test engineer to scrutinise it, or having to roll a release and put it live. It keeps productivity up by limiting the scope of ‘done’. They can queue up tasks for a future release, or a whole round of acceptance testing.

The next thing it does is it allows the rest of the team to see what tasks are dev-done and are available to be reviewed or tested—something might have been built and is functionally complete, but no one has started reviewing that work yet. Anything in Implementation done says ‘Hey, my developer thinks I’m complete, so someone please feel free to come along and test me.’ This column becomes the to do list for the next people on the process.

(User) Acceptance Testing

User acceptance testing (UAT) is when a client or Product Owner takes a look at the task and either approves or disapproves it based on whatever criteria you’re working toward. Anything that fails UAT would typically be moved back into the Sprint backlog column until someone is available to amend whatever was wrong with the work.

Ready for Release

Ready for release, predictably, is any work that has been done, approved,

and is waiting to be put live. For me, this usually means merging it into

master or a x.x.x version branch.

Released

Released is what most people call Done. It’s out there, it’s in front of a user, it’s finished.

This might be putting something live on an actual client site, or it might be me publicly releasing a new feature of inuitcss.

The Labels

When I used to use a physical board, we had different coloured index cards to represent different types of task. Yellow index cards represented features or additions, pink represented bugs, and blue represented (Dev)Ops work.

Trello’s cards are all the same colour, but they do have six different coloured labels you can apply to them. You can also assign each colour its own meaning. These are the meanings I’ve assigned to the six available colours:

- Green: Feature/improvement

- Yellow: Copy/content

- Orange: Product

- Red: Bug

- Purple: Design

- Blue: Dev

I find that these six labels—when used creatively—can cover pretty much all eventualities. You might have to class any Ops work as Dev, or UX/IA as Design, but it seems to work for me, and I can always change things around if I need to.

You can also use multiple labels on any one card, to give multiple meanings. Red and purple implies a design bug: perhaps the logo is fuzzy on retina devices. Green and blue and purple means that we’re to design and build a new feature: perhaps a carousel for the homepage.

Feature/Improvement

Anything labelled Feature/improvement is something that isn’t in the product now, but should be. It’s additional functionality or behaviour that somehow improves or enhances the product. Most things tend to fall under this category.

Copy/Content

This label means that the card concerns itself with the creation or acquiring of content, for example, writing up the FAQs, or getting employee biographies from the client.

Product

I find this is the most rarely used label, but it deals with any non-dev, ‘soft’ requirements. A decent example might be Decide on pricing tiers. This isn’t a design, dev, or content issue, it’s a product related task that might be part of the sprint, but is purely product focused. You may well have another card entitled Price comparison matrix which deals with the design and build of displaying these pricing tiers, but the tiers themselves are a product task, not a technical one.

Bug/Tech Debt/Blocked

Red was the clear choice for this type of card: anything that is labelled red typically needs fairly immediate attention.

A bug is obvious: something broken in the code (or design) that needs fixing. It’s not a new feature, but a fix for something that is currently live and broken.

Technical debt is like a bug, but not quite. It’s something in a codebase that isn’t broken per se, but is less-than-ideal. Perhaps, in a rush to get a feature live, you hard-coded some values that should be dynamic. You know that you need to go back and tidy these things up, but they’re not necessarily bugs.

I’ve written about hacks—and how they’re inevitable—before, and these are exactly the kinds of thing we mean when we talk about tech debt.

Blocked cards are ones which are held up—or blocked—by other cards on the board. Perhaps we have have a feature/improvement card entitled Case studies which is a task to design and display some testimonials and case studies on your client’s marketing site. You might also have a content/copy card entitled Get client logos which is a task to get assets and content from the client. You can’t design and/or build the case studies section until the client has provided you with the content, so the Case studies card is blocked by the Get client logos card.

Design

The Design label, as I’m sure you can imagine, is any task that requires design work. As I mentioned before, this does cast a very wide net, so this might include IA, UX, UI, illustration, preparing assets, etc.

Dev

Similarly, the Dev label is a pretty broad category. This could cover Ops, front-end development, DB architecture, etc. Your mileage may vary, but this seems to work just fine on the projects I’ve been working on.

Members

Assigning members to cards shows you who is—or should be—working on a particular task. It is not uncommon for a card to have a number of labels and members attached to it: perhaps Jenna and Steve are a developer and designer working together on the landing page.

Assigning people to cards lets them know what they need to be aware of, and also lets the rest of the team know what everyone else is up to at a glance.

Reading a Kanban Board

The beauty of a Kanban board—aside from their excellent way of organising things—is that they are easily read at a glance. A Kanban board gives a great visual overview of the state and health of a project without having to read or research a single thing. Is there a mass of cards piling up in Implementation done? Perhaps your Product Owner needs a hand UATing stuff, or you need more test engineers. A load of red labels on the board? Perhaps you need to write more tests to avoid bugs. One person’s avatar appearing more than anyone else’s? Perhaps you need to try and lighten their workload.

A well-managed board allows you to spot bottlenecks in your process, and gauge the state of a project very, very quickly.

Filtering

The beauty of Trello, which a physical board cannot provide, is that it can be filtered. This means you can choose to view all design bugs assigned to Jane, or all dev bugs across the entire project, or all outstanding content issues. This really is a great feature for Project Managers/Product Owners/Scrum Masters, but also for individuals to find out what their current workload is like. For example, if I have a spare half-an-hour, I might filter to find all tech debt tasks assigned to me in order to see if I can find anything that I could quickly refactor.

Extending This

This is just my setup, and only the parts of it that are general enough to share. There are some more specific things I do, but they’re too detailed to be of any use in this post.

As with anything, your mileage may vary: you might have a completely different setup that works perfectly for you already, or you might find little value in a Product label, for example, but the beauty of Trello—and agile as a broader concept—is that you can shape it to fit your needs.

I hope this article has proved useful for some, and that you can take it and extend it for your own work.

Agile and process is something I’m really, really enjoying working on with my clients at the moment, so if you feel like you could use some help then please do get in touch with me—I’d love to work together on this kind of stuff.

N.B. All code can now be licensed under the permissive MIT license. Read more about licensing CSS Wizardry code samples…

By Harry Roberts

Harry Roberts is an independent consultant web performance engineer. He helps companies of all shapes and sizes find and fix site speed issues.

Hi there, I’m Harry Roberts. I am an award-winning Consultant Web Performance Engineer, designer, developer, writer, and speaker from the UK. I write, Tweet, speak, and share code about measuring and improving site-speed. You should hire me.

You can now find me on Mastodon.

Projects

- ITCSS – coming soon…

Next Appearance

-

Talk

Devoxx Greece: Athens (Greece), April 2025

Devoxx Greece: Athens (Greece), April 2025